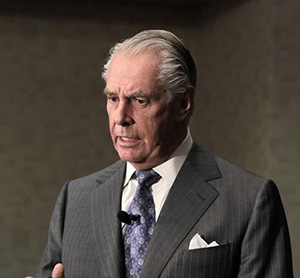

Dr. Matt T. Rosenberg, MD, presented “How to Differentiate the Causes of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms” at the 26th Annual Perspectives in Urology: Point-Counterpoint, November 10, 2017 in Scottsdale, AZ

Keywords: Urinary Tract Symptoms, PSA, BPH, OAB

How to Cite: Rosenberg, Matt T. “How to Differentiate the Causes of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms” November 10, 2017. Accessed Apr 2024. https://dev.grandroundsinurology.com/differentiate-causes-lower-urinary-tract-symptoms

Summary:

Dr. Matt T. Rosenberg, MD discusses the Causes of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms, Flow vs. Volume, and When to diagnose BPH vs. OAB.

How to Differentiate the Causes of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms

Transcript:

First of all, I want to thank David Crawford for bringing me up. He very aptly pointed to the clock for how much time I have since I go over. I will go over on the last talk, since you had me do testosterone today, but there’s a lot of important information, Dave.

All right, so we’re going to talk about lower urinary tract symptoms, BPH vs. OAB, Flow vs. Volume. The reason I want to bring this up–is this mic–there we go–when a patient goes to the primary care doc, what happens, unfortunately, is they come in with lower urinary tract symptoms, whatever it is–urgency, frequency, nocturia. If it’s a woman, you’re diagnosed with OAB. If it’s a male, they’re diagnosed with BPH. That’s just how we’ve been trained to do this.

The reality is there’s a simpler way to do that, a simpler way to elicit this. One of the things that I try to do–and I’m going to keep pointing at you, since you and I are doing the same thing here. Very frequently, people can have a mix of those or maybe none of these. Maybe when you come in with lower urinary tract symptoms, it’s a medical problem. Just because you’re a urologist and the world you see is between the belly button and the knee caps, it doesn’t actually mean that the LUTS symptoms are just that, from the prostate, if you have one, or the bladder. There’s a medical cause of lower urinary tract symptoms very often.

One of the things that I do suggest to my urologic colleagues is, when we talk about shared care–and Dave was talking about in cancer work–shared care is also with lower urinary tract symptoms. Maybe you do have OAB. Maybe you are going to the bathroom quite a bit and having urgency because of low bladder volumes. The fact is it’s not bothersome until you had a heart attack, and you’re on hydrochlorothiazide, and you’re pushing all that fluid through. That interaction between family docs, internal medicine, and urologists are certainly very important.

Let’s see. This is not working. Where was I–Ryan, did you take the right one? I did press the green. Can I have some technical–oh, you’re just screwing with me now. All right, let’s go back to my first slide please, since we’re now well into it.

All right, so let’s just kind of go back to a 101. Here’s OAB. If we’re going to be talking about OAB, we need to define it. It’s a syndrome or symptom complex defined as “urgency, with or without urgent incontinence, usually with frequency and nocturia.” Urgency is the big symptom. This is what drives people into the office. I had a guy the other day who came in. Why are you here? What’s changed over time? He’s like, I can’t be rushing to the bathroom anymore. It’s becoming embarrassing at work. Urgency is that symptom that I hear frequently.

It’s common. This is important for us to realize, both in urology and primary care. This is very common in a lot of people who are undiagnosed. I was in the clinic yesterday until five. I saw all of these diseases, and I guarantee you that there were quite a few OAB–and OAB that I might not have known about because they might’ve been hiding it.

We think about OAB being a female disease. It’s actually both a male and s female disease. It’s more prevalent in women as they’re younger. As we get older, it’s men and women. Why is a slide like this important? It’s because if that 70 year old male comes into your office and we fail treatment for BPH, we have to scratch our heads and say maybe something else is going on. It could very well be OAB.

What about the prostate? We just heard a wonderful talk on the prostate, just to kind of review a few things. It gets bigger as we get older, all right? It doesn’t mean it becomes symptomatic. Only about 10 % of patients will become symptomatic. It has two options. It’s either going to grow out or grown in. If it grows in, it causes blockage. If it causes blockage, you have poor flow. That’s where you get symptomatic.

There’s a wonderful slide from Claus Roehrborn I’ve used for many years now. I think it’s extremely important to teach this. If your PSA is elevated, which is a surrogate marker for prostate size–we’ll talk about that later. If your prostate is about 30 grams at 55 years of age, you can expect it to be about 61 grams by the time you’re 70. Why is that important? If you’re symptomatic at 55, you’re going to be more symptomatic at 70. You may not need treatment, but we should tell the patient ahead of time that this is what we can expect and be aware of it. If there’s a problem, well, let me know.

This comes from–oh, Dave, it’s one of your papers. Look at that. I quote this all the time. This is actually a very important paper, so I do have to give him credit for this. This is the risk evaluation for BPH. If you have these five risk factors, it’s predicted that your prostate will become more symptomatic. A total prostate volume of 31, a PSA of greater than or equal to 1.6, age of 62. That, a primary care doctor can readily do. We don’t generally do flow, although, Michigan, we have snow. I tell people if you can write your name in the snow in script, as opposed to Braille, you’re probably pretty good. Number four, Dave, since you wrote this paper, can we say Braille signature in the snow?

CRAWFORD: Yes.

ROSENBERG: Good, and a post void residual of greater than 39, that’s a risk factor as well. As we’re dealing with lots of symptoms, we should acknowledge the fact that these things can coexist. I’m sorry, the OAB part of that didn’t come out very well. The reality is this. You can have a big prostate. As Ryan said, it doesn’t have to be obstructed. If it does, you can have symptoms of LUTS. If you have OAB, you can have symptoms of LUTS. You can certainly have them together.

Now the question I’m asked frequently is, well, if OAB is so common, why don’t we see it? Why is it not out there? That’s because people cope. Last night, I got on a plane. I flew from Detroit to here. The reality is that there were a lot of people on that flight who stopped drinking fluids a couple hours before who went to the bathroom as soon as they said we’re going to do pre-check. We’re going to get people in with their dog, their multiple handicap dogs or whatever they’re coming on with these days.

They ran to the bathroom to empty their bladder again. They had diapers in their bags. They had pads. They had dark clothing. I guarantee you that they did that because people cope.

They know where all the bathrooms are. They bathroom map, all right? As I said, they restrict their fluid. They try to get on a schedule. Unfortunately, when it becomes a problem for them, when they come into the office is because they can’t cope anymore.

I just had a patient about two weeks ago who I kind of knew was having a problem, but she was coping with it. They moved into a new factory. She works at a tool and die in Jackson. She went from a position that was near the toilet to a position that was away from the toilet, about 100 yards. These are big factories. Now she has to walk around everybody to get to the bathroom, whereas before, she was able to hide it. These coping mechanisms no longer work for her.

If we’re going to understand LUTS, and this is something to talk to your primary care about. Remember, the primary care doctor in family practice has had maybe two weeks, probably no training in urologic care. The internal medicine doc had no training in urologic care. Yet, as Dave had mentioned, 30 % of what I do in the day has to deal with that area between the belly button and the knee caps. If we’re going to deal with LUTS, we have to understand normal function of the bladder and normal function of the prostate.

What does the bladder do? It holds urine. Alan Wein said this years ago and it was brilliant. It holds urine and it empties urine. It doesn’t do anything else. It doesn’t walk; it doesn’t talk. It doesn’t absorb. It does it comfortably. I should be able to hold 3 to 500 ml. I should be able to empty 3 to 500 ml. I should be able to go to the bathroom comfortably and not feel like I have to hold my crotch as I’m running across the room. That’s what it should do.

Abnormal function is when it doesn’t do that. I’m holding less than the 3 to 500. I have this uncontrollable urge. The bladder is all about volume. Everything we talk about with the bladder is about volume.

In regards to the prostate, Ryan Terlecki just went through this. There are two functions for the prostate. One is fluid for seminal emission. I would add a function for you, Ryan. I think you only gave that one. The second function is to stay the hell out of the way. It does a really bad job at that, and it becomes obstructed. The symptoms are very easy. The bladder is about volume. You can have urgency, frequency, nocturia of small volumes. Remember that–of small volumes.

Voiding, prostate, poor flow, hesitancy getting that flow out, problem getting the flow out, straining to get the flow out–bladder is storage and volume. Voiding flow is the prostate. We wrote this up a couple years ago, and I think it holds true now. If we differentiate this thing–this is what I tell my colleagues as I’m teaching them in primary care.

Look, you don’t have to spend a lot of time on this. If it’s of a weak flow, you got to focus on the prostate. If you’re voiding small amounts, think the bladder. If you’re leaking urine, think the bladder or the sphincter. If you have good flow and normal volume–this is where the medical doc comes in, the family practice internal medicine doc–if you have good flow and good volume, what are you thinking? It’s a medical issue. We’ve got to refocus. That is not a urologic issue now. You have good volume. The bladder is doing what it’s supposed to do. You have good flow. The prostate is staying out of the way. It is a medical problem, and you need to treat that accordingly.

In 2007, a group of us got together. We wrote up an algorithm for primary care. We very simply called it the LUTS algorithm. Now I’ll walk you through this. The idea is, looking at LUTS, it’s like looking at an onion. We’re peeling away the onion. Maybe this is causing it; maybe that’s causing it. What is the core of this that’s giving us the problem of urgency, frequency, nocturia, whatever symptoms you have? We start with symptoms.

We start with, are you having frequency nocturia, urgency of small volumes? This comes from the Urodynamic Society. This comes from their guidelines and the ICS. Frequency, nocturia, urgency, I don’t really buy this very well though. I don’t look at frequency as less than eight times a day. I look at frequency of small volumes. If you’re voiding 500 mL every hour, that is not OAB or BPH. That is actually a medical issue. Nocturia and urgency, again, the same thing–what are the volumes?

These are some questions that you can ask. I’ve written this up several times. I suggest these only as ideas for the doctor to talk about. Everyone’s going to come up with their own questions. You’ve got to talk to the patient on terminology that they’ll understand. Do you have a sudden urge to void? Do you wear a pad or a diaper? Can you sit through a movie? I know these sound like very basic questions, but it’s amazing.

I had a patient years ago who had told me that everything was fine. She was in her physical earlier in the year, and she comes in three months later. She said I’m having a problem. I said, well, what was your problem? She goes, well, I’m rushing to the bathroom, and I’m wetting myself. I said, when did it become a problem?

She goes, when I started overflowing my diaper. I’m like, I didn’t know you wore a diaper. She goes, you never asked me. Her idea of normal was a diaper. We really have to have some good, quality questions here.

This is he IPSS. I think everybody here is familiar with it. I guarantee you most primary care don’t use it. I guarantee you they’ll understand the questions. As you talk to your colleagues who referred you, let them know that there are some questions that they can use such as the IPSS to help them delineate prostatic symptoms.

Now what about the history, physical, and labs? As we’re doing this, what can we do in a primary care setting? There’s certainly the medical and the surgical history. There’s medications, focused physical exam. These are all things that’ll help us. The key point with this slide–I’m going to go through the points in just a minute, but–urodynamics, cystoscopy, and diagnostic renal and bladder ultrasound are not necessary.

This was made clear by the AUA a couple years ago, although it took them until 2012 before they finally admitted you didn’t need a comprehensive workup in the uncomplicated patient. This means that, in a primary care setting, we can evaluate that patient with LUTS very simply–what I like to say is in two minutes or less with duct tape and popsicle sticks–and be able to make an appropriate evaluation.

Now when does the medical problem become involved? This is stuff I do. This is not stuff necessarily the urologist does. Diabetes, you’ll have the polyuria/polydipsia. If you had a recent heart attack, you’re going to have a low EF afterward. You’re going to develop some congestive failure. You’re going to have pitting edema in the lower extremities. This means when you go to bed at night and you lift your legs, it all rushes up, and it flows out, so you’re peeing at night. That’s not your bladder; that’s not your prostate. Although, you may have had a little bit of a problem before, but it’s been exacerbated by the fact of fluid mobilization.

These are things I need to know. Surgery is very common. I see this constantly in orthopedic surgery because you go in and you get your hip done, right? The orthopedist sends you home, right? You’re immobile. You’re sitting there holding your hip watching TV and get that first urge to void. You don’t want to get up because it hurts. You get the second urge to void, and you still don’t want to get up. You finally get up after the third urge which, as you know, there is no third urge. You’ve wet yourself because you can’t get to the bathroom.

Or, the orthopedist gives you 100 Norco, and you want to be a patient and take your 100 Norco which you shouldn’t be doing. Then you haven’t had a bowel movement in a week, right? You call up the orthopedist and say I haven’t had a bowel movement. He says tough luck, go call your primary care doc, and we disimpact them which we’ve done and we hate. There’s a temporal relationship to the symptoms and what’s going on and the onset of what we would consider lower urinary tract symptoms.

Medications, it can be anything on any list. I look at the temporal relationship. This time of year, cold and flu season, allergies in Michigan–you’ll probably be seeing that down here in Arizona soon. You take the second-generation antihistamine with a D on it. If a male and the D on it, you can’t pee. Your stream is low. You go to the doctor, not realizing it’s your cold medicine. I look at that temporal relationship as well.

Physical exam is very simple. The nice thing in primary care is this is what we do all the time. We don’t need to repeat things that have been done, but we want to look at the abdomen for tenderness, masses, distension. We want to make sure the bladder’s not up to the xiphoid. Make sure they know to get to the bathroom. Make sure they can walk to the bathroom. I’ve had three patients with MS I’ve diagnosed who came in with lower urinary tract symptoms. Two had cerebellar ataxia; one had fecal incontinence, all right? Neurologically, there was a problem going on. We can assess that. You don’t need to do the type of neurologic exam a neurologist is going to do, but you want to do something and make sure that they’re okay.

A general urinary exam, unfortunately with all the guideline changes, primary care think you don’t have to ever pull somebody’s pants down. I am against that. We should be pulling their pants down. That’s why you come to a doctor’s office. You want to feel like you really got tortured. Well, make sure the opening is open. Make sure the meatus is open. We are not doing that. Please help your colleagues understand that. Look at the meatus. Make sure the foreskin retracts. Make sure, in a female, you look at the meatus. I’ve seen a woman who came in from a gynecologist actually. She had lower urinary tract symptoms. I did an evaluation. I told her I needed to do a vaginal exam. She said I just had one with my gynecologist. I said your gynecologist made a mistake. She goes, what mistake did he make? I said he didn’t use my hands.

That’s the good part about it. The bad part is I found a urethral tumor, all right? Those things do happen. The rectal exam, please do those. Please, please, please do those and make sure your colleagues do those. I don’t need to tell you guys why to do it. Our primary care colleagues don’t seem to like it.

The AUA put out the guidelines for lab tests a couple years ago. I disagreed with them because they only look at the urinalysis. You cannot screen for diabetes with the UA. I published in the White Journal that. They still ignore me. The bottom line is you have to have a blood sugar of 180 before you’re spilling into the urine, so be very careful with that. Use a fasting or random blood sugar.

PSA, we’re going to talk about quite a bit. I’ll talk about it in my next talk. This is not screening anymore. This whole screening argument goes away. This is a patient coming in with LUTS, so check a PSA. If the PSA is 1.5 or more, it equates to a prostate gram size of 30. That’s a person at risk.

Voiding diaries, I love these. You have everyone do these. Go home, pee in a hat, your little bladder hat, and collect how much. See what the volumes are. Is it 50? Is it 100? Is it 200? You should be 300, and it should be 24 hours, 7 days a week. It shouldn’t just be when you get a triple latte on your way home from work, all right? If you have OAB, it’s going to happen all the time. If you want to manage how your OAB treatment is going, then a voiding diary certainly helps us as well.

Post-void residuals, there’s this urban myth that we’re going to put people under attention. That is not true. That is not true; it’s been debunked. A lot of guys in years’ past were not getting treatment for OAB. They were only getting treatment for BPH. That is false. If you have a good flow, the chances of you going into retention is very, very low. If there’s any concern, check a post-void residual. I did a meta-analysis a couple years ago, which I published, and if your post-void residual is less than 50, the chances of you having a problem are very, very low. Primary care don’t have a post-void residual, but they can get a residual at a local diagnostic ultrasound area.

The most important slide I can show you to share with your primary care colleagues is how to stay out of trouble, simple evaluation tools, effective treatment, and safety. Show them when to refer to you. That’s the list here. You guys can read that, but it’s very, very important. Make sure to share that with them.

The reality is now, once we’ve done this evaluation, the treatment can be empiric. There’s no identifiable etiology, no reversible causes. We ask the patient, with your LUTS that you’re presenting with, are you bothered enough that you want treatment? No, okay, fine, I’ll see you in a little bit. Let’s keep in touch on this. If it is, if it’s flow, think prostate. If it’s voiding volumes, think the bladder. If it’s incontinence, think the bladder or the outlet.

I’ll go back to the algorithm just for this. Frequently, my colleagues will be wondering, how do I know it’s not the prostate? Well, you don’t. You don’t necessarily always know. If they have a good flow, it’s unlikely. If you worry about it, treat the prostate first. Then think about the bladder afterward.

I’m going to end with this before I go to Ryan. What are the treatment guidelines? I know Ryan’s going to go more into this before–behavioral treatment, bladder hygiene. Teach people how to void. Teach them to take their time, rest the pelvic musculature. Count to ten and pee again. It’s very, very important. Sit on the toilet if you need to, all right? Males get uptight about that. Sit on the toilet. That’ll help.

Females, you’d be amazed–women do not sit on toilets that they did not buy. They feel like they’re going to get an STD or get pregnant. That is false. That is absolutely false. The bottom line is to tell them it’s okay to sit on the toilet and relax. Don’t keep your legs together and stress all the pelvic musculature like this. You need to relax and do it in the privacy of your own home. Do it in the privacy of a stall, but relax the pelvic musculature.

If we go to pharmacologic management, if it’s OAB, we have antimuscarinics and β-3s. You can use them in monotherapy or combination. BPH, alpha blockers, PDE 5s, 5 ARIs, I’ve used all of them in combination before. If it’s OAB and BPH, I will use a combination of med, and I will tell my colleagues that. I’ll try them to exhaust several efforts before they finally refer off to the specialist.

My final slide, we ignore BPH and OAB. We have to be aware of that. It doesn’t take your life. It steals your life. On the other hand, if you do have OAB and you do have BPH and you’re going to the bathroom a lot, unfortunately, that’s when, if you’re old, you tend to fall down. If you fall down, you break something. If you break something, you die. The mortality of a hip fracture in an elderly male is 70 %. It’s 50 % in a female. These patients are in the primary care office. Unfortunately, we don’t ask as well as we should, but they can very simply be identified and treated.

I want to thank you.