Dr. Ashish M. Kamat, MD, presented “Barriers to Clinical Trials for Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer” at the 2nd Annual International Bladder Cancer Update on January 27, 2018, in Beaver Creek, Colorado.

How to cite: Kamat, Ashish M. “Barriers to Clinical Trials for Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer” January 27, 2018. Accessed Dec 2024. https://dev.grandroundsinurology.com/barriers-clinical-trials-non-muscle-invasive-bladder-cancer/

Summary:

Ashish M. Kamat, MD, articulates the discrepancies in the American Urological Association (AUA) and European Association of Urology (EAU) bladder cancer treatment guidelines, challenges in defining a risk-stratification scale for the disease, knowledge gaps regarding bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) failure, and other factors that hinder the urological community’s ability to design quality clinical trials for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC).

Reveal the Answer to Audience Response Question #1

Which is the most correct statement about the situation that you face?

- A. Majority of patients with disease persistent at three months can be salvaged by maintenance BCG.

- B. Papillary disease recurrence at three months confers a high risk of subsequent progression.

- C. BCG failure at 3 months is best treated with intravesical chemotherapy.

- D. Or blue light cystoscopy detects clinically insignificant tumors.

Answer Explanation:

The answer is Option B. Option A, the majority of patients with disease present at three months can be salvaged with maintenance BCG, is partly true, and I’ll go over that in my talk a little bit. However, it doesn’t apply so much for papillary disease, but it definitely applies for carcinoma in situ.

Reveal the Answer to Audience Response Question #2

- A. Papillary disease recurrence at three months is a failure.

- B. The majority of patients with carcinoma in situ present at three months can be salvaged by maintenance BCG.

- C. The majority of patients with papillary lesions at three months can be salvaged with maintenance BCG.

- D. Timing of recurrence has prognostic implications.

Reveal the Answer to Audience Response Question #3

- A. NMIBC is a heterogeneous disease with deferring risk of progression and recurrence.

- B. The FDA has clearly defined criteria, which must be met regarding efficacy endpoints for bladder cancer trials.

- C. Papillary tumors and carcinoma in situ have to be studied in separate groups since they seldom co-exist.

- D. Risk groups used by the AUA and the EAU are similar, but they differ from that used by the NCCN.

Answer Explanation:

The answer is Option A. The statement that is true is that non-muscle invasive bladder cancer is heterogeneous disease with very different risks of recurrence and progression. The FDA has not clearly defined anything so far. Papillary tumors and carcinoma in situ can be studied in the same group. We just have to analyze them separately and actually the risk groups used by the AUA and the EAU are very different.

Barriers to Clinical Trials for Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer – Transcript

Click on slide to expand

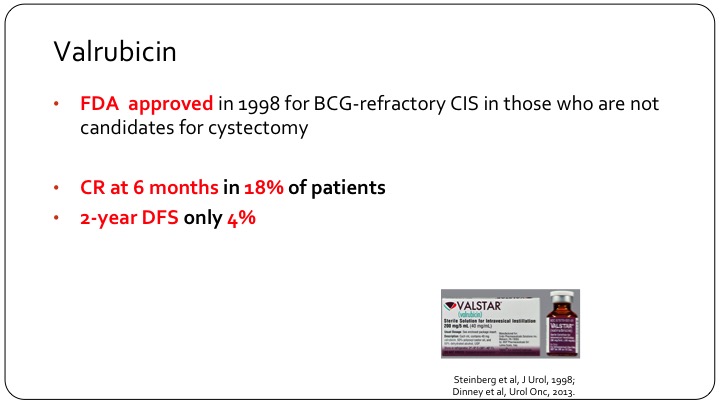

Valrubicin

So let me start my talk with a little bit of a story. So valrubicin as you all know was approved by the FDA in 1998 for BCG refractory carcinoma in situ in patients who are not candidates for a radical cystectomy. But if you look at the results of valrubicin, CR at 6 months was only seen in 18% of patients, and the two-year disease free survival was only 4%.

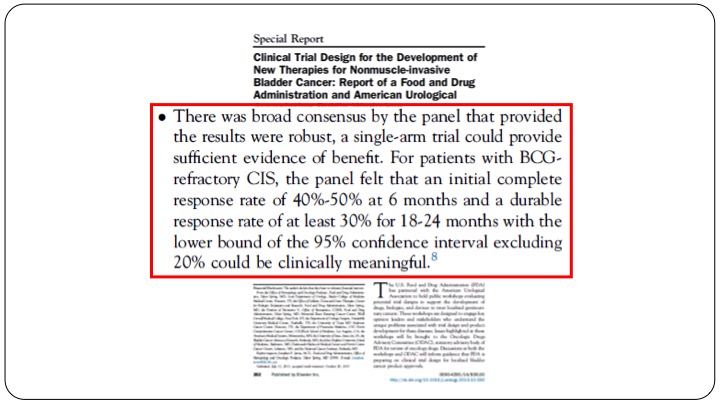

Development of New Therapies for Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer

So clearly recognizing that they sort of messed up with this, the AUA and the FDA came together at the behest of the FDA and they had a workshop that was held in several members in the audience were part of that workshop. And they came out with a broad consensus statement stating that for patients with BCG refractory CIS, the panel felt that an initial complete response rate of 40 to 50% at 6 months and a durable response rate of 30% at 18 to 24 months with the confidence intervals at 20% would be clinically meaningful. So they set this arbitrary number and several on the panel had a discussion as many of you may be aware. There wasn’t that much agreement but this is what the FDA came up with.

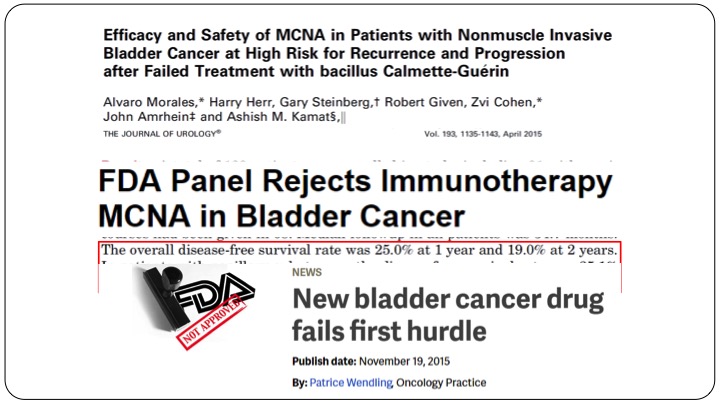

Efficacy and Safety of MCNA in Patients with MCNA in Patients with Non-muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer at High Risk for Recurrence and Progression after Failed Treatment with bacillus Calmette-Guerin

Fast forward several years later, MCNA or urocidin, again many of you in the audience participated in the clinical trials here came up with their result, and they found that the overall disease free survival rate was 25% at one year and 19% at two years in all-comers and in patients with papillary only disease, the disease-free survival rate was 35%. So clearly better than valrubicin, and maintained at 32% at one and two years. Unfortunately because the FDA had set their limits, which was fairly arbitrary, this drug was not approved. This drug was rejected, not approved, and it was all over the headlines that after many, many years we had a drug that had come up for approval, and as rejected by the FDA.

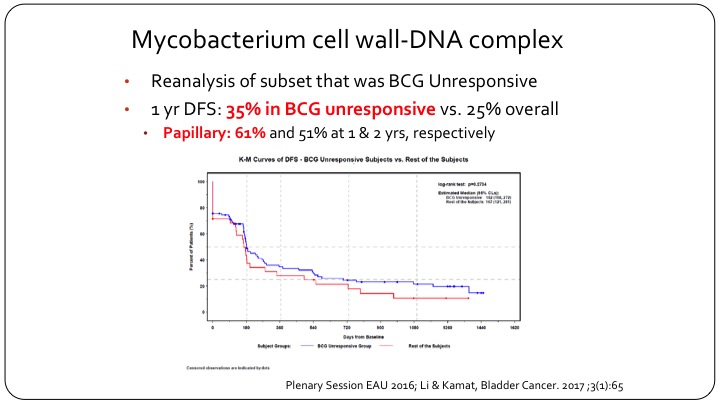

Mycobaterium cell wall-DNA complex

But if you go back and you look at the actual results of this clinical trial and you look at the BCG unresponsive population, and Dr. Lerner will talk about that in more detail, but if you look at what the FDA now recognizes as being BCG unresponsive, actually MCNA or urocidin had a 35% disease free survival in this group, which clearly meets the FDA’s threshold. And in fact in papillary only patients the disease-free survival was 61% at one year, and it was maintained to 50%+ at two years. So clearly if the FDA went and listened to their own criteria and their own recent definition, this drug should have been approved, but it wasn’t approved because of the problems that we face with clinical trial design in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer.

NMIBC is NOT a homogenous disease state

What is the first barrier that we face when it comes to designing clinical trials for bladder cancer? Number one, as you very appropriately recognized in the ARS questions, non-muscle invasive bladder cancer is not a homogeneous disease state.

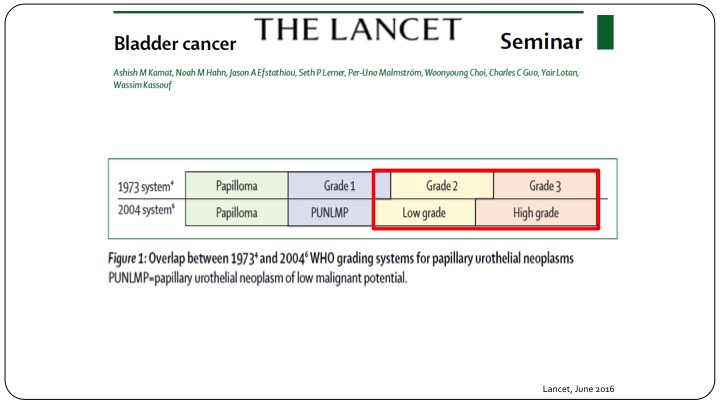

The Lancet

When you look at something quite as simple as grade, you can clearly see that when we talk about Grade 1, 2, and 3, or we talk about low grade and high grade, there is not a very overlapping situation. Many patients called low grade are either grade 2 or grade 1, and when you say high grade you still have some grade 2 patients and grade 3 patients. So when you are looking at all of the results or all of the reports that use the 1973 system and say Grade 1, and Grade 2, and Grade 3, you can’t just translate that into what we currently use, which is low grade and high grade, and this is true not only when you are looking at results of clinical trials, but also actually designing clinical trials going forward.

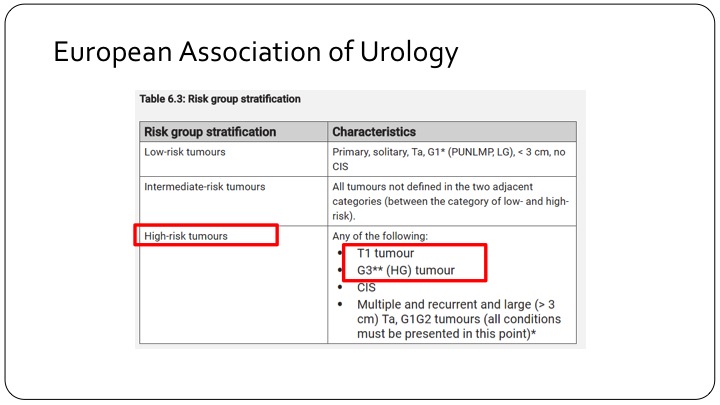

European Association of Urology

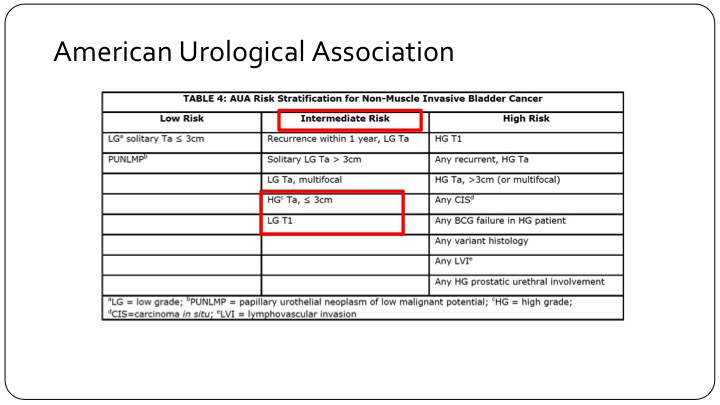

This is where the discordance between the European Association risk criteria and the American risk criteria come in. If you look at the EAU’s risk criteria, high-risk tumors are those that are T1 tumors, makes sense, and all grade 3 tumors which of course includes carcinoma in situ. So if we are looking at a European trial that talks about high-risk tumors, you are talking about T1 tumors, high-grade tumors.

American Urological Association

And if you look at the American Urological Association, patients who are high grade but TA and less than three centimeters are actually called intermediate risk category patients, and low-grade T1 tumors, which are very rare, but still do exist are also in the intermediate risk category. So clearly the intermediate risk category trial design using the AUA criteria is not going to have the same end points either in your design or when you read it out, as those that are designed across the pond in Europe or using the European criteria.

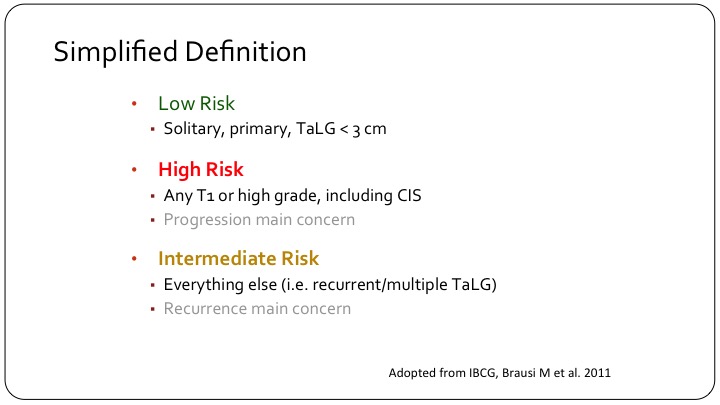

Simplified Definition

In order to come up with a sort of a simplified definition, what many of us use clinically is a low-risk patient is that solitary primary single small a TaLG tumor. A high risk patient is any T1 or high grade including carcinoma in situ, and then you have this intermediate category of patients that some of us were discussing yesterday, which is the hodgepodge, which is the majority of patients that we see, and it’s really hard to make sense of this sub-group of patients.

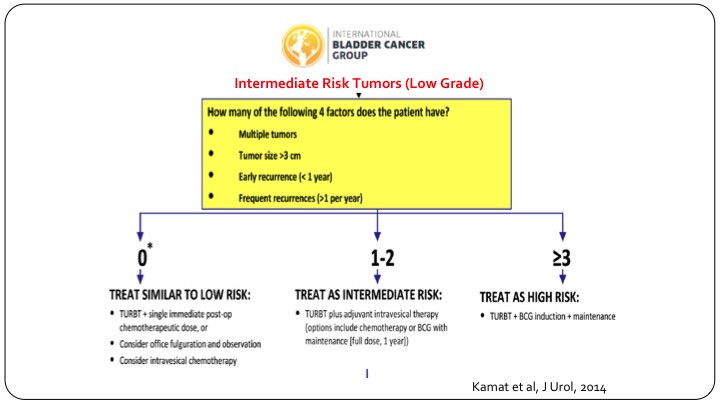

Bladder Cancer Group

In order to try and delineate these patients, and this is more for clinical trial design, the international bladder cancer group came together and looked at all of the published data that existed, and we identified four risk factors. Number one, multiple tumors, tumor size more than three centimeters, early recurrence, less than one year, or frequent recurrences, that is more than one per year, and if you have none of these risk factors, these patients behave very similar to low-risk patients, and you can treat them as such. If you have three or more risk factors they do behave like they are high-risk patients and you should design your clinical trial along those lines. If they have just one or two risk factors so multiple tumors or multiply enlarged but don’t have the others, then they truly behave like they could be anywhere in between, and that is where your clinical trial needs to have a wide statistical confidence interval built into it.

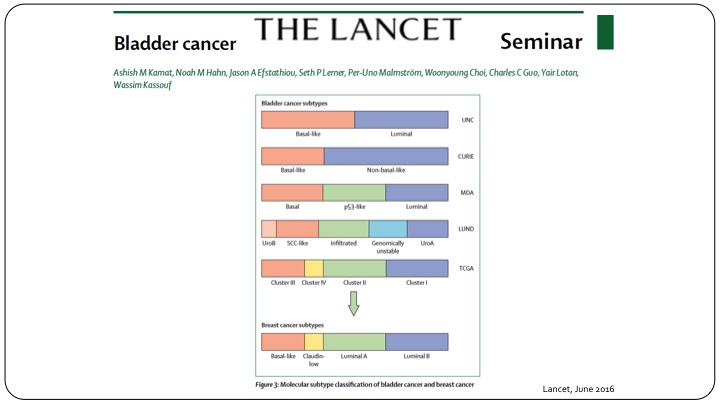

Bladder Cancer Subtypes

This is using clinical parameters but of course we know moving forward in the future we will have to follow the same paradigm that we have when it comes to invasive disease in subtyping of these patients using the genomic profile.

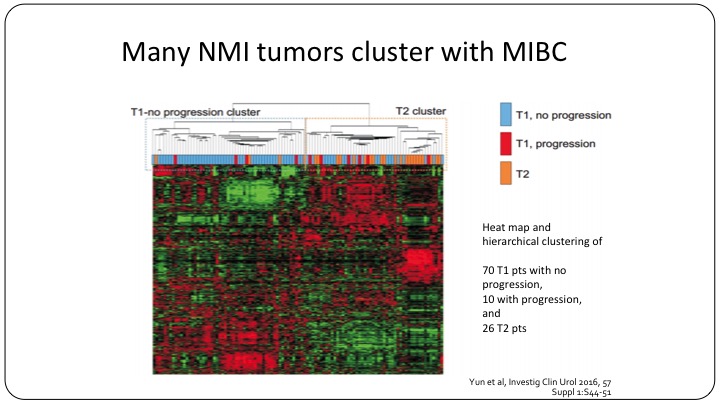

Many NMI tumors cluster with MIBC

Even now we know that many non-muscle invasive bladder cancer tumors cluster with the muscle invasive category. So moving forward, yes, we can use T1, TA, CIS, but I believe that we will be using sub-classifications to further refine our clinical trials.

The ‘Gold Standard’ for tumor detection is flawed

Now, what is barrier number two? Barrier number two is that our gold standard, which is our cystoscopy that we performed before you enrolled the patient on the clinical trial, or you actually give them adjuvant therapy in your clinical, is actually very flawed.

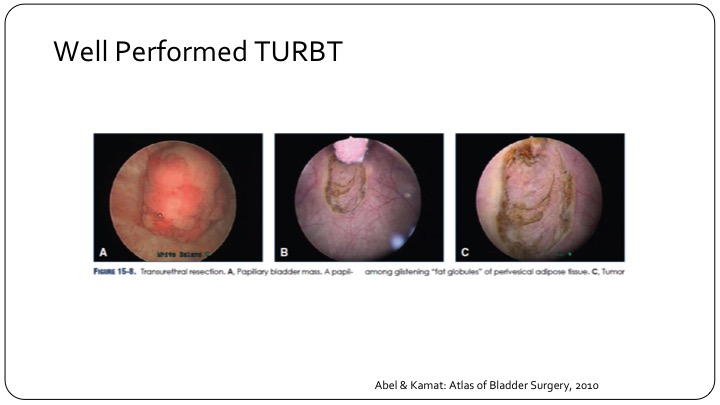

Well Performed TURBT

A well-performed TURBT with muscle present in the specimen, etc., is a well-recognized tool that we teach our residents and fellows.

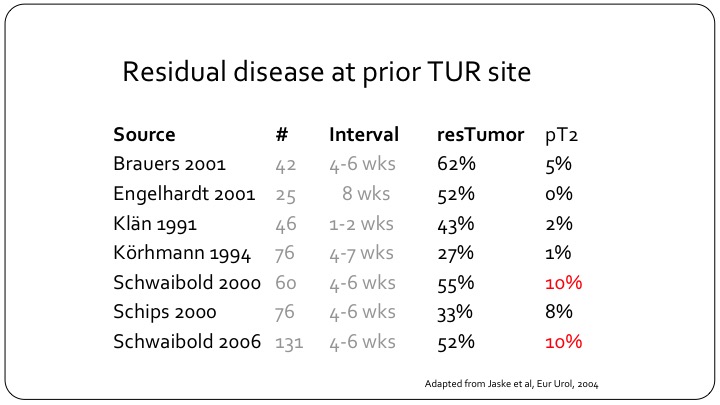

Residual disease at prior TUR site

But, despite that and this is a slightly older study from 2004 but it is very important, residual disease can be found in as many as 62% of patients, and these are not small universities that are reporting on their results. And muscle invasive bladder cancer can be found in as many as 10% of patients so clearly if you have a patient that you are treating as non-muscle invasive disease either in your practice or on a clinical trial and that patient hasn’t had the appropriate TUR, you could be treating one out of ten patients that have muscle invasive disease as though they were non-muscle invasive, and clearly the outcomes will not be as good.

Repeat TURBT

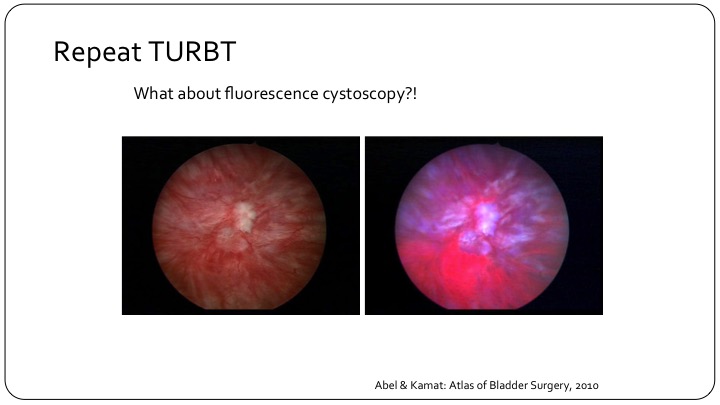

So repeat TURBT has sort of entered all of the guidelines. There’s a little debate sometimes at different plenary sessions as to whether it is appropriate for all high-grade patients or all T1 patients, but the bottom line is it has entered our guidelines, and I think it is appropriate. But what about using fluorescence cystoscopy? If you look at this here, you can clearly see that if you look in with a white light, you may not be able to see the leading edge of what is obvious on the fluorescence cystoscopy as the pink leading edge over here.

Surveillance Cystoscopy

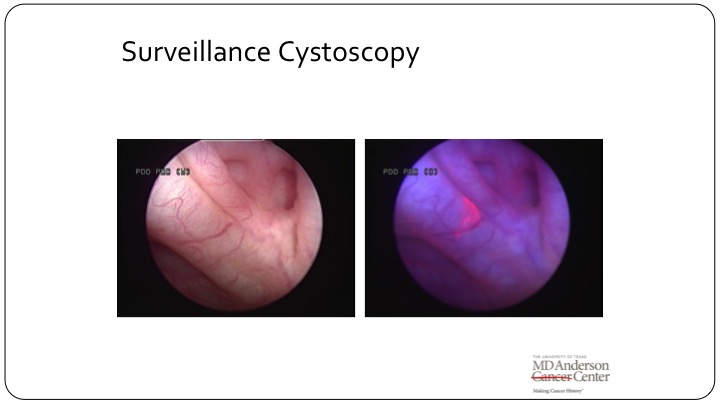

And even as relevant is on surveillance cystoscopy. So this is a picture of a bladder that I looked in, and to me it looked like it was NED. You turn on the blue light, and there is clearly a little patch there. You biopsy; it’s CSI. This patient clearly has carcinoma in situ. This patient clearly on a clinical trial would be a positive endpoint and then either fall off the clinical trial or go on to be counted as an alternative arm. So how does fluorescence cystoscopy or MVI, whatever you use, fall into your armamentarium today? That’s very important to recognize.

BCG Failure Has Only Recently Been Standardized

Barrier number three is that the definition of BCG failure has only recently been standardized, but I do want to emphasize a few points as it pertains to clinical trial design.

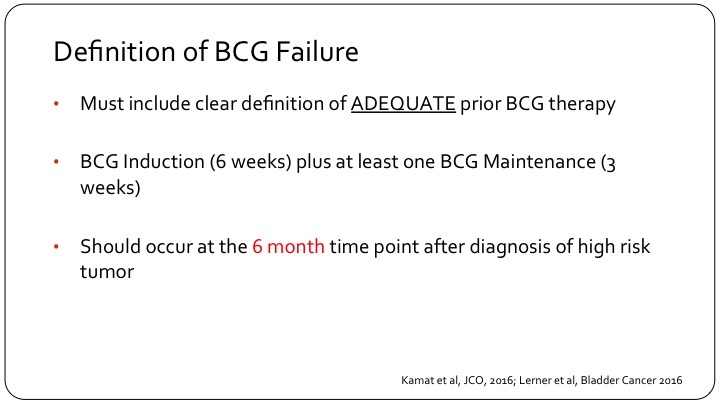

Definition of BCG Failure

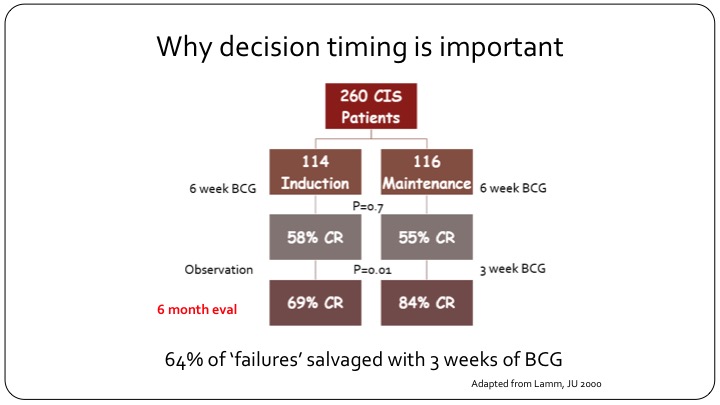

Number one, when we are talking about BCG failure we must clearly have a definition or state what was adequate to prior BCG therapy, and that should be BCG induction, which ideally should be six weeks, and at least one maintenance BCG installation, so that is three weeks of BCG. Now, the FDA does allow 5 out of 6 and 2 out of 3 just in order to allow us to enroll patients in clinical trials because they are not treated appropriately in the real world, but this is what should be included in the definition of BCG failure. And calling something or a patient unfortunately as having not responded to BCG or BCG having failed a patient should occur at the six-month time point and using the three-month time point or the three-month cystoscopy to call something a failure is fraught with difficulties, and let me show you an example.

Why decision timing is important

This is a flow chart that is adopted from Don Lamm’s publication. If you look at the carcinoma in situ patients in the study, and you can look at any publication with carcinoma in situ and you will have similar results, but this is using that one, they had 260 CIS patients. It was a randomized study of maintenance versus no maintenance, so both arms got induction BCG. After six weeks of evaluation and at the first cystoscopy the CR to BCG as expected was 55 to 58%, and that is what we see in the clinic today. You give your patient with carcinoma in situ BCG induction of 6 weeks, and more than half of them will have a response at the first cystoscopy. Now, look what happens when you just observe these patients and do nothing. If you observe these patients and do nothing, at the next follow-up cystoscopy, the CR has jumped from 58% to 69%, so there is an increase in response just with the picture of time because that is the way BCG and inflammation and the immunotherapy in the bladder works. But now look what happens when you give these patients just three more weeks of BCG. So with one maintenance installation or one course that’s three weeks, the CR goes from 55% all the way up to 84%. So clearly if you had called this patient a BCG failure at the three-month cystoscopy and put them on drug X, and you’ve gotten a CR in that group of say 30%, you would think that your drug worked. But 64% of these so-called failures can be salvaged just by giving another three weeks of BCG. So clearly calling this patient a candidate for BCG failure trial at three months would have misclassified this patient because this patient clearly would have benefitted from just three more weeks of BCG and that is about 64%.

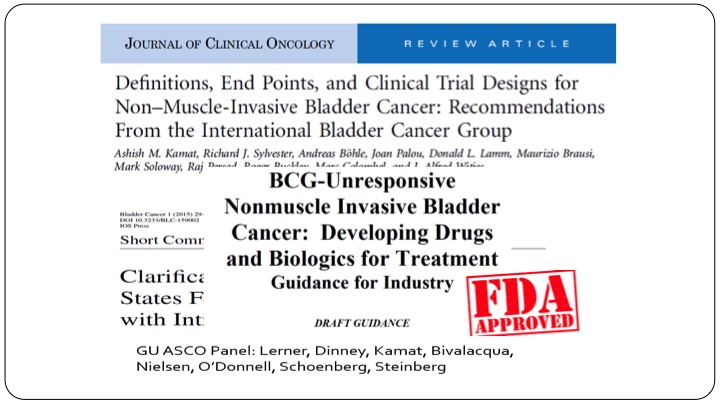

Journal of Clinical Oncology

Because of that groups have gotten together at the GU ASCO, the National Bladder Cancer Group, and the FDA has adopted the BCG unresponsive definition and the timing in their white paper, which they published not this last November, but the November before that, and we have been in touch with them periodically and I’m promised that the revised draft guidance should be out some time in the next month or two. If it’s out, that would be great, but they have these criteria in there, and again, I don’t want to go into too much of those details.

Predictive Markers Remain Elusive

Lastly, barrier four, we’d like to be able to predict how our patients will do. We’d like to try and design these endpoints in the clinical trials, we like to put correlative studies. All of that is great, but as of today, as of 2018, predictive markers have remained elusive.

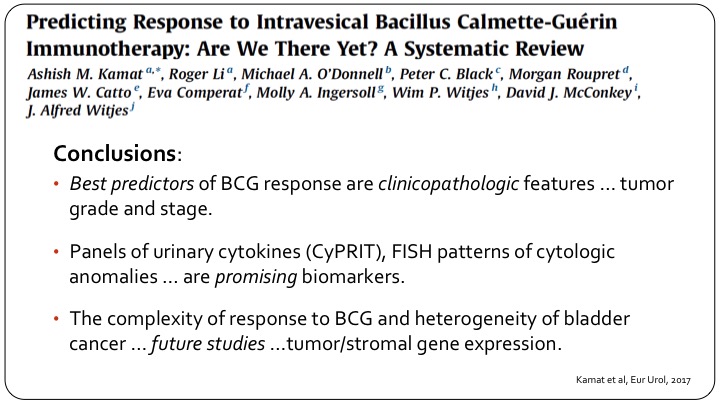

Predicting Response to Intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guerin Immunotherapy: Are We There Yet? A Systematic Review

I thought I would just show this one slide. It’s a collaborative effort that we put together at the behest of the European Association of Urology, several members are in the audience here, and really looking at all of the published data, all of the work we are doing, etc., and this was published late last year, all we could conclude was the best predictors of BCG response are clinical pathological features, tumor grade and stage. Great. What’s new? Panels of urinary cytokines, the separate assay, FISH patterns are promising biomarkers and these have been shown in small studies including ours to be useful, but they haven’t been validated in a large group, and of course as we always do in these reviews if you don’t have anything useful now, we say future studies are important. They are important. I’m being a little tongue in cheek, but the bottom line is we don’t really have predictive markers today.

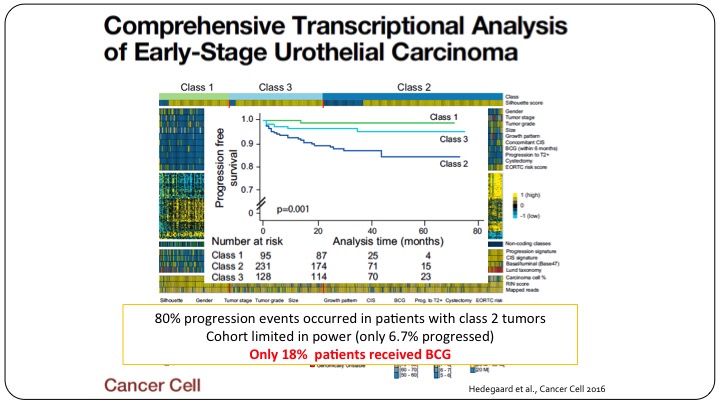

Comprehensive Transcriptional Analysis of Early-Stage Urothelial Carcinoma

And let me show you an example, even if we do have papers, and this was a really good publication in a really high-impact journal, Cancer Cell, that looked at clustering patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer, and they tried to have three classes of patients, Class 1, Class 3, Class 2, showing a differential outcomes of these patients based on their genomic profile. Unfortunately, this too cannot be used as a predictive marker because these cohorts were not well representative of what we do today. Only 18% of these patients actually got BCG. So yes, we have a relatively prognostic sub-classification of these patients but it clearly doesn’t predict anything because these patients didn’t get the treatment that we’d give them nowadays.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ashish M. Kamat is a Professor of Urology and the Director of the Urologic Oncology Fellowship at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center He is Associate Editor for European Urology Oncology and Co-President of the International Bladder Cancer Network

Dr. Kamat’s focus in urologic oncology is on bladder cancer, especially immunotherapy, and he maintains an active research portfolio in this area. His research laboratory focuses on identifying and developing predictive markers of response to therapy, and research into mechanisms of inducible cancer stem cells. He also serves as project PI on the MD Anderson Cancer Center GU (Bladder) SPORE. Dr. Kamat’s findings have been published in high impact journals and he has over 225 publications to his credit. Dr. Kamat is listed in ‘Who’s Who in Medicine’ and ‘Best Doctors in America’ and has won the ‘Compassionate Doctor Award’ from patient groups.

Dr. Kamat actively participates in various global urologic efforts, serving on the boards of regional and national societies for urology and urologic oncology and also in patient advocacy groups (BCAN).