Dr. Daniel P. Petrylak presented “Checkpoint Inhibitors” at the International Bladder Cancer Update meeting on Tuesday, January 24, 2017.

Keywords: bladder cancer, atezolizumab, chemotherapy, inhibitors, metastatic, pembrolizumab

How to cite: Petrylak, Daniel P. “Checkpoint Inhibitors” January 24, 2017. Accessed Jan 2025. https://dev.grandroundsinurology.com/checkpoint-inhibitors

Summary:

Dr. Daniel P. Petrylak discusses urology practices moving from standard chemotherapy and toward studying checkpoint inhibitors’ efficacy when treating tumors, especially regarding bladder cancer.

Checkpoint Inhibitors

Edited Transcript:

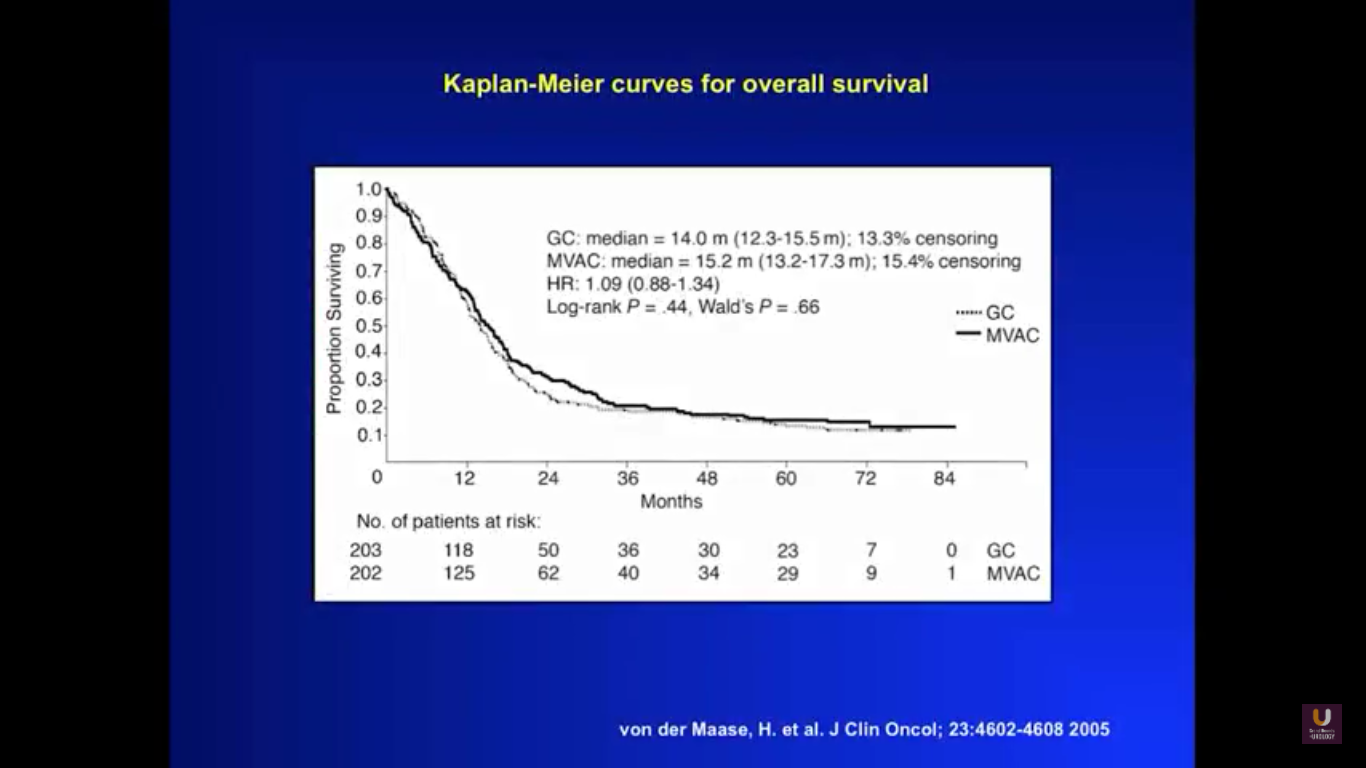

To get a sense of our starting point for this lecture, take a look at this graph. It shows survival curves for a patient with metastatic disease, treated with primary chemotherapy. You could substitute any cisplatin-based regimen into this particular equation, whether that be dose-dense MVAC or standard MVAC, and rarely would you see five-year survival. That only happens with about 10% of all patients.

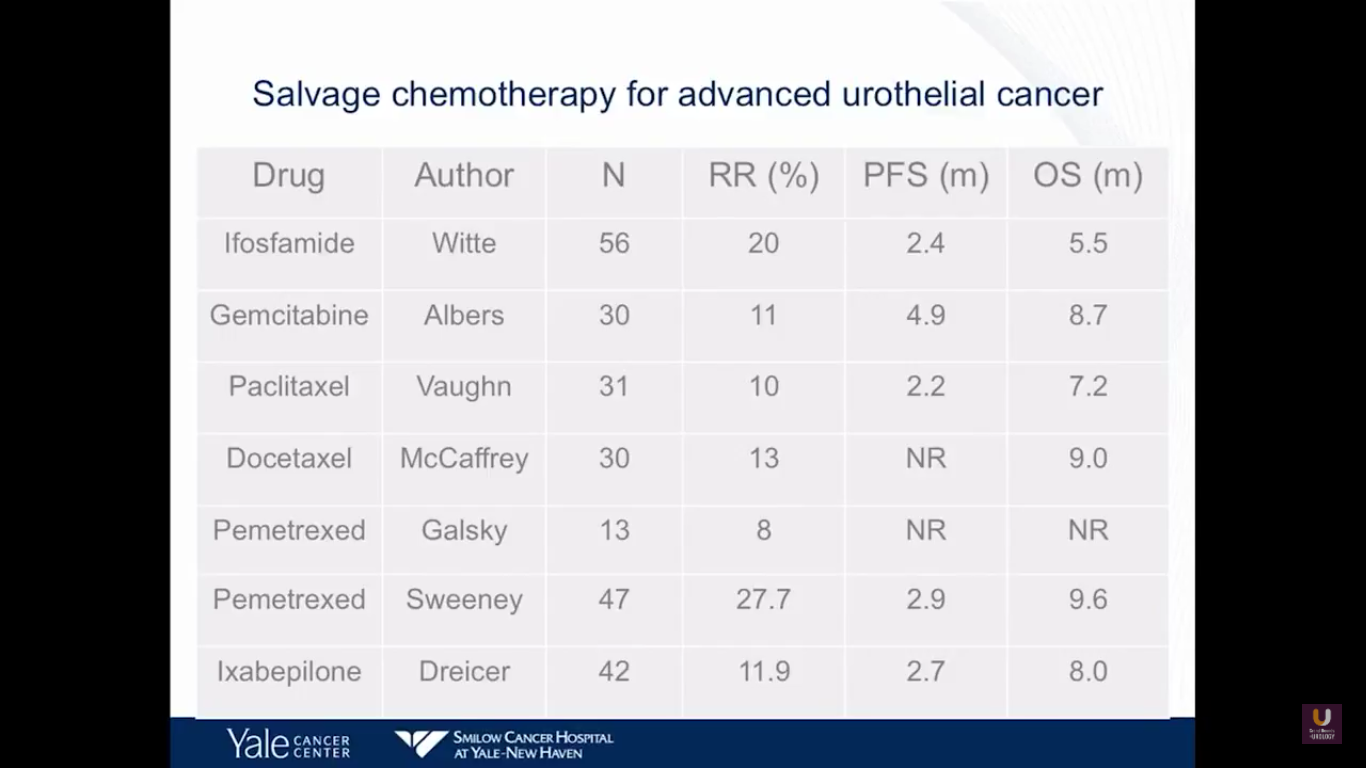

This next slide is Prozac-worthy. If you look at the salvage for patients with metastatic bladder cancer who fail primary chemotherapy, there are few agents that really have an efficacy. Perhaps pemetrexed and docetaxel have a degree of efficacy, with about nine-month overall survivals. But, none of these drugs will cure patients. At best, they will temporize things.

These disheartening statistics raise the questions, “What about other treatment options? Where are we moving?”

Well, immunotherapy might be the answer to that question.

Most recently, there have been significant advances in using immunotherapy to manage bladder cancer. We also know that other tumors with a high mutational rate, such as melanoma and lung cancer, notably respond to checkpoint inhibitors.

So, what are checkpoint inhibitors?

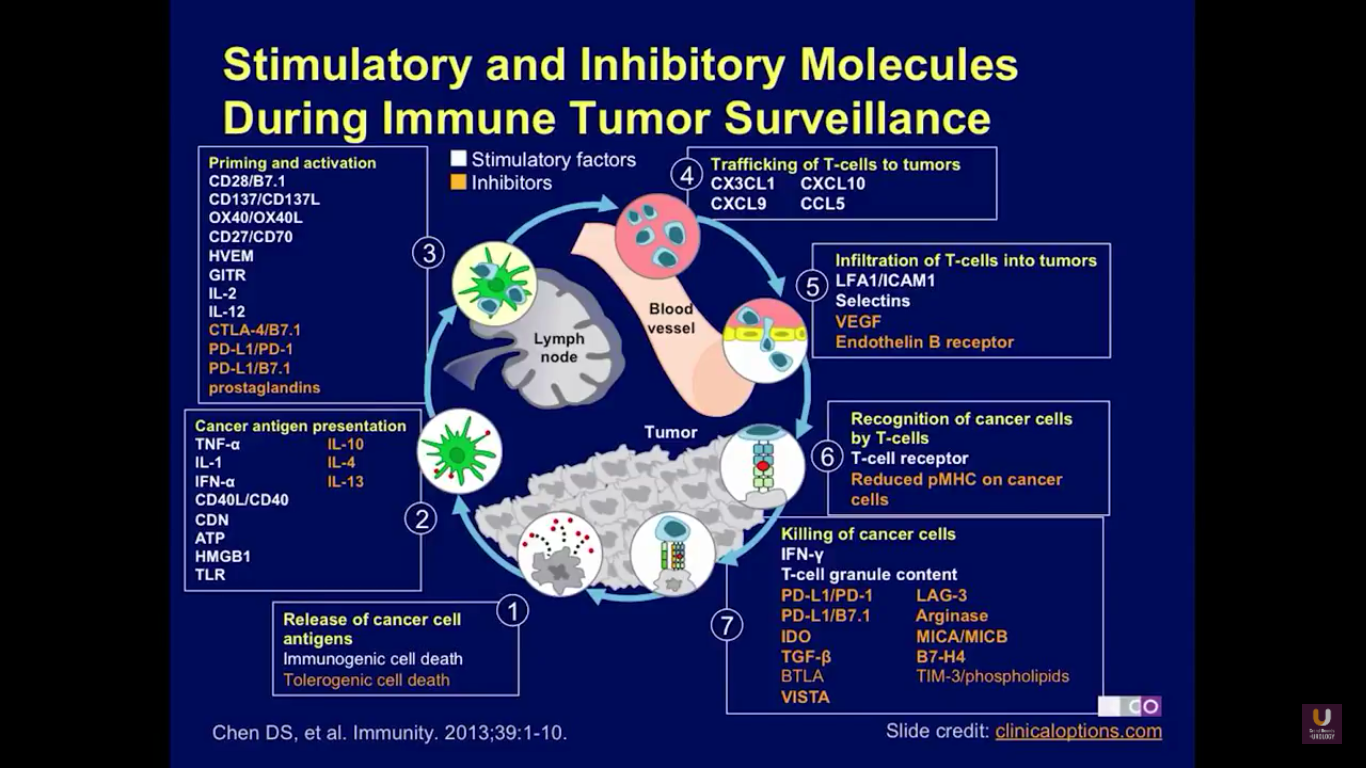

Checkpoint inhibitors are agents that will regulate the immune system. Here, you can see the pathway of immune regulation. The pathway starts when cancer cells release antigens into the lymph node and into circulation. This is due to immunological cell death. Then, the antigens are presented, and a variety of different agents regulate that presentation to the lymphocytes. These include tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-1, and interferon alpha. Agents that will negatively affect that interaction include IL-10, IL-4, and IL-13. Next, the immune cells are primed and activated. Agents that will inhibit that activation include CTLA4, PD-1, and PD-L1, and the prostaglandins.

Eventually, these T-cells are trafficked to the tumor cells. Then, T cell cause death by infiltrating the tumor. Perforins will then cause the cells to lyse and to die. These are also negatively regulated by VEGF. Finally, the cancer cells are recognized by the T cells, creating immune surveillance, and causing the removal of cancer cells from both lymph nodes and any metastatic site in the circulation.

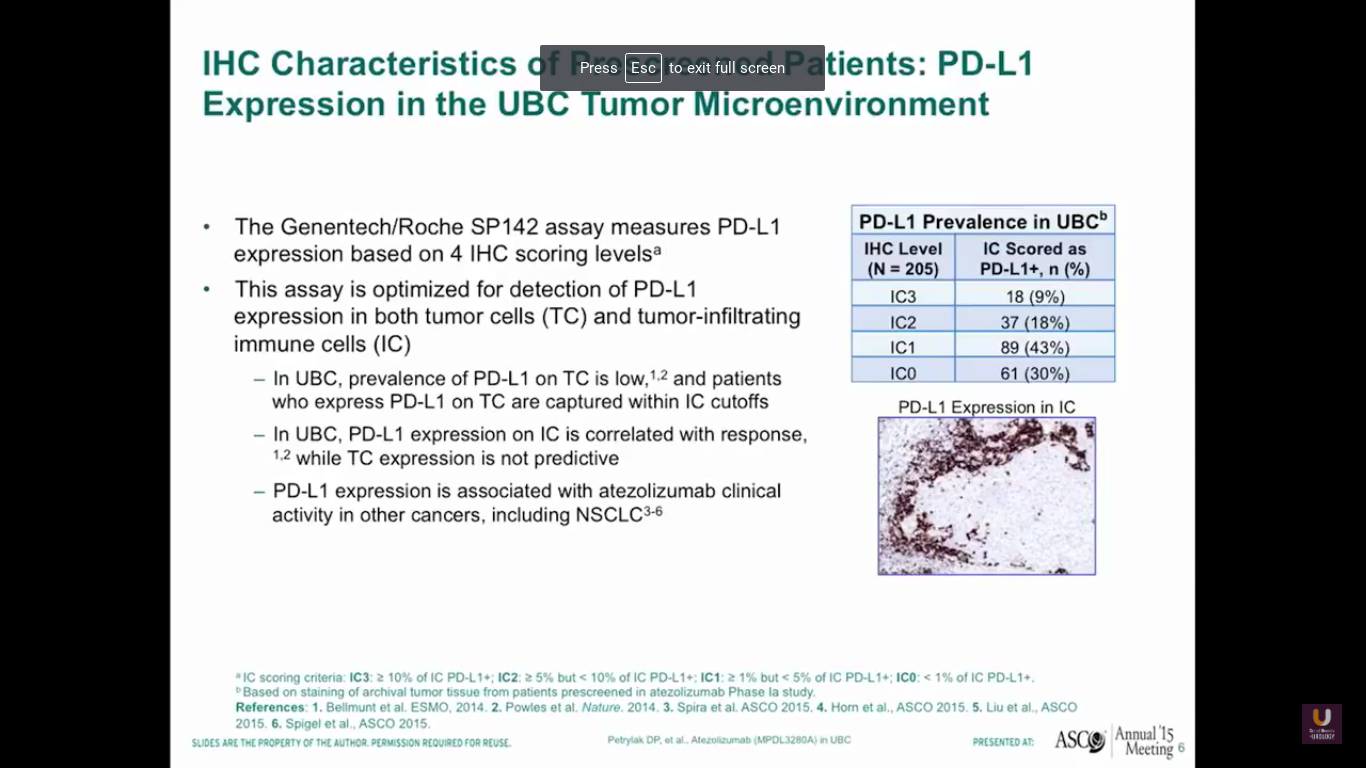

Now, what about PD-L1 and PD-1 expression in bladder cancer? This data from our phase I experiment looking at PD-L1 and atezolizumab, which is a PD-L1 inhibitor. By using this SP142 assay, we found that a third of bladder cancer patients had high levels of expression of PD-L1, a third of patients had intermediate levels, and a third of patients had no expression.

Now surprisingly, this was not in the tumor cells. This was in the immune cells that were present with bladder cancer. Other studies have shown that there is tumor cell expression of PD-L1. I think this is assay dependent, as well as when we look at these particular specimens in the course of their treatment overall.

Our first study started in 2013, or four years ago from today. It was published in Nature by Tom Powells. Interestingly, our best patient on this trial just relapsed. He had failed three chemotherapeutic regimens and developed metastatic disease in his lymph nodes. He was a complete response. Unfortunately, he just relapsed and is going onto one of the secondary trials. We’ll talk about those trials a little bit later.

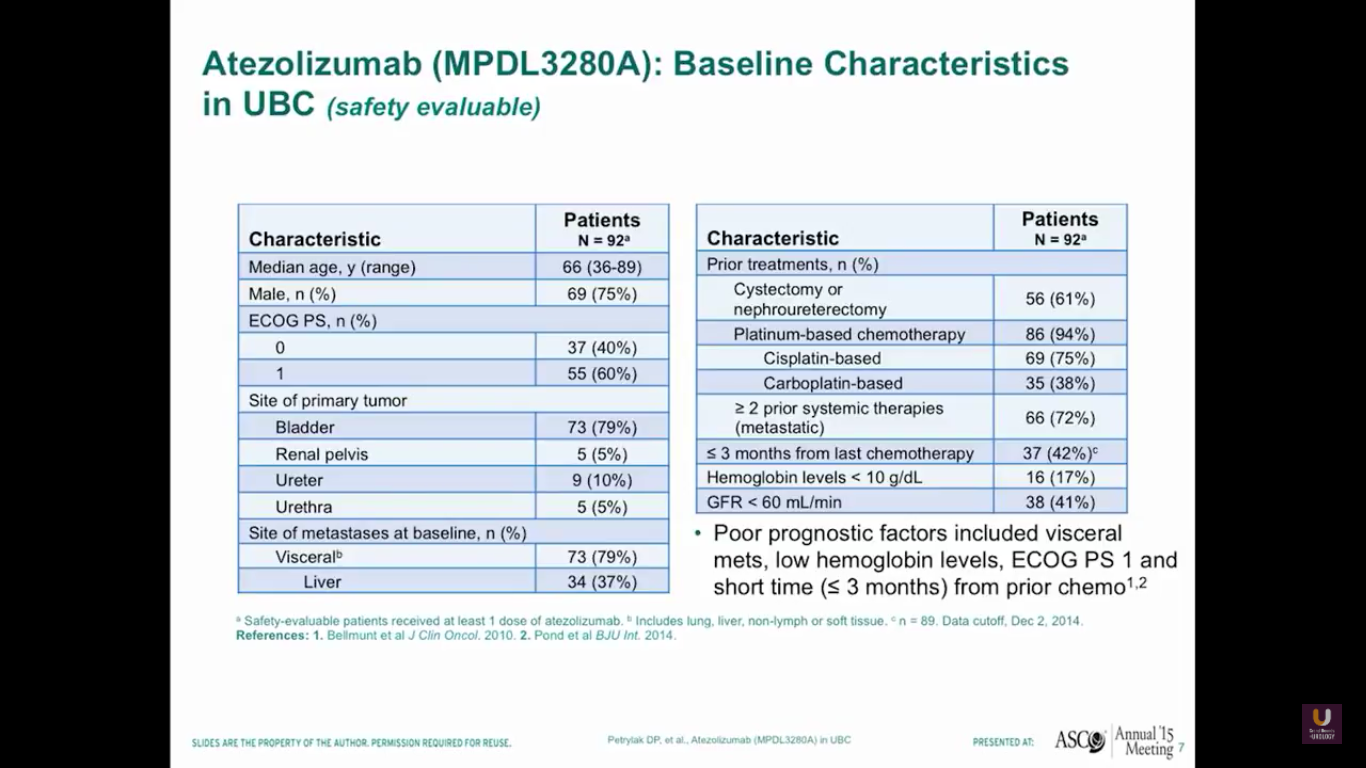

Our first 92 patients predominantly have bladder primaries. The median age of the patients is 66, and 79% of them have a disease in the bladder. In the group of advanced patients, 79% have visceral disease, 37% have metastases to the liver, and 94% have received prior platinum-based chemotherapy. Of those with poor prognostic factors, 42% have less than three months from their last prior chemotherapy, and 17% have hemoglobins of less than 10.

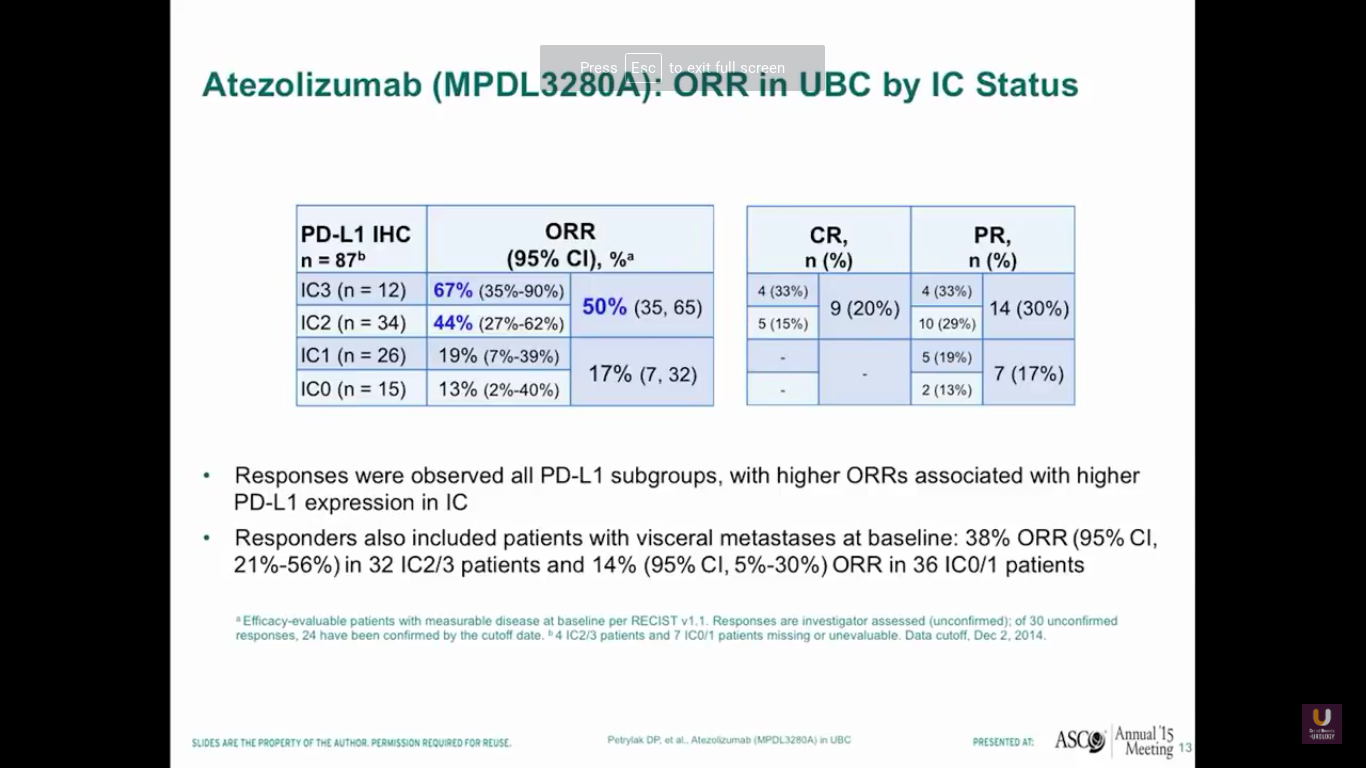

So, after giving atezolizumab intravenously every three weeks, we see that about half of patients with high levels of expression of PD-L1 in the immune cells responded. In fact, we saw complete responses in 20% of those patients. Now, this is the point where staining becomes less reliable. We should not be using PD-L1 staining to select patients for standard treatments, because 17% of those patients who were weakly positive or negative for PD-L1 had a response to treatment. Responders also included patients who had visceral disease, 38% of patients overall, and also patients who had low levels of PD-L1 expression, like we said before.

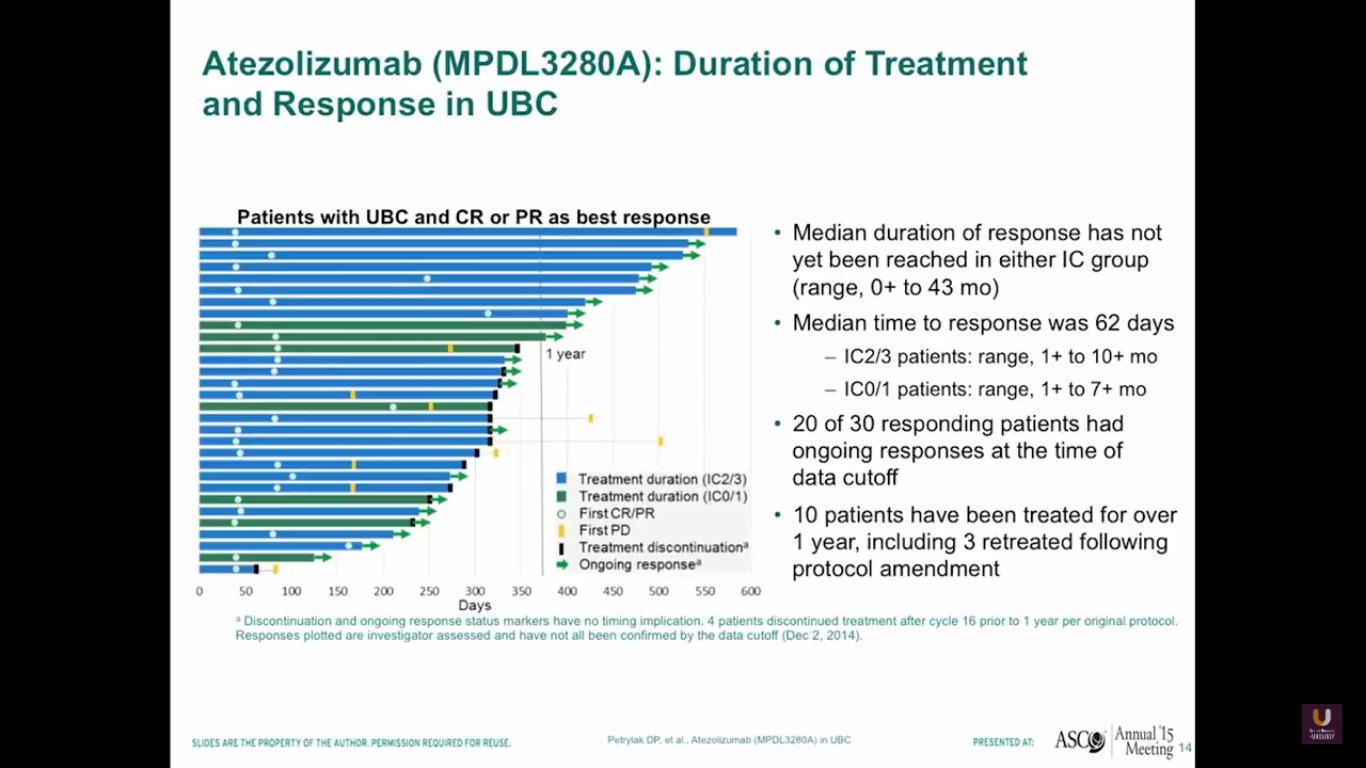

I gave this presentation at ASCO about two years ago. We’re going to update this information at ASCO GU this year. Anyway, the median duration of response had not yet been reached. Interestingly, the duration of response is independent of PD-L1 status. So, if you respond, you’ve got a good chance of continuing your response for a fairly long period of time.

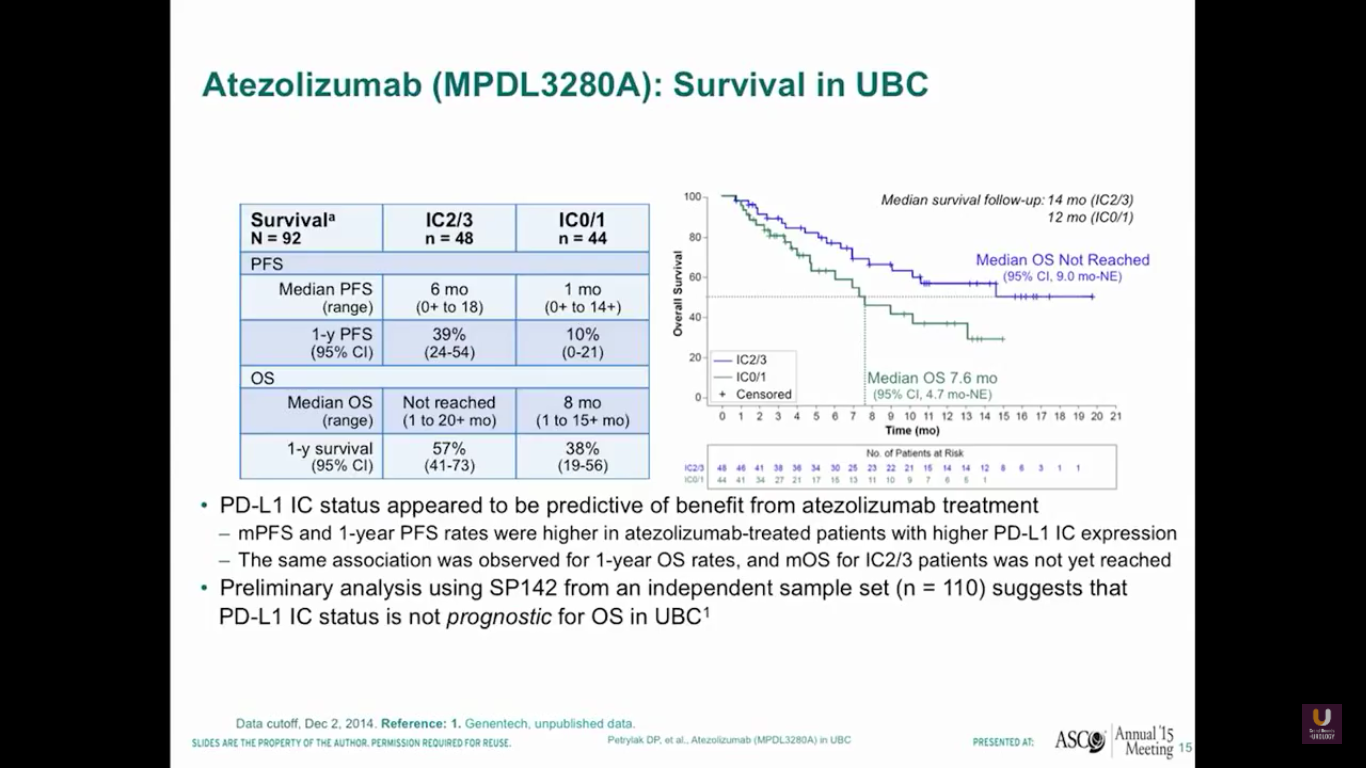

I’m going to update this survival data at this year’s ASCO GU meeting. But, as this data stands, we see that the median overall survival has not yet been reached for patients who have high levels of expression to PD-L1.

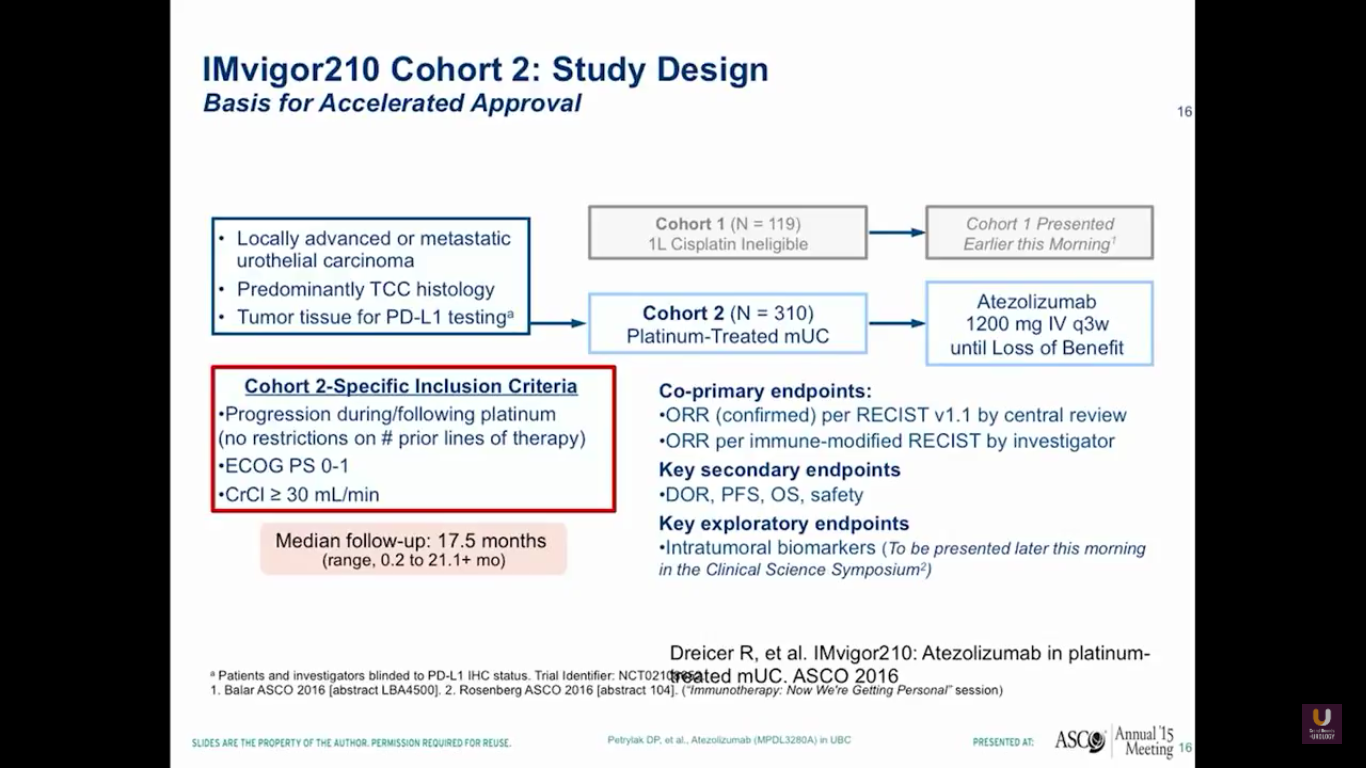

This prompted us to go onto a larger trial, which Jonathan Rosenberg led. This was the IMvigor210 trial. It had actually two sections to it. One section was for platinum experienced patients, while the other section of patients were platinum ineligible. I think that this is going to be very important for the elderly patient that we talked about earlier in the session.

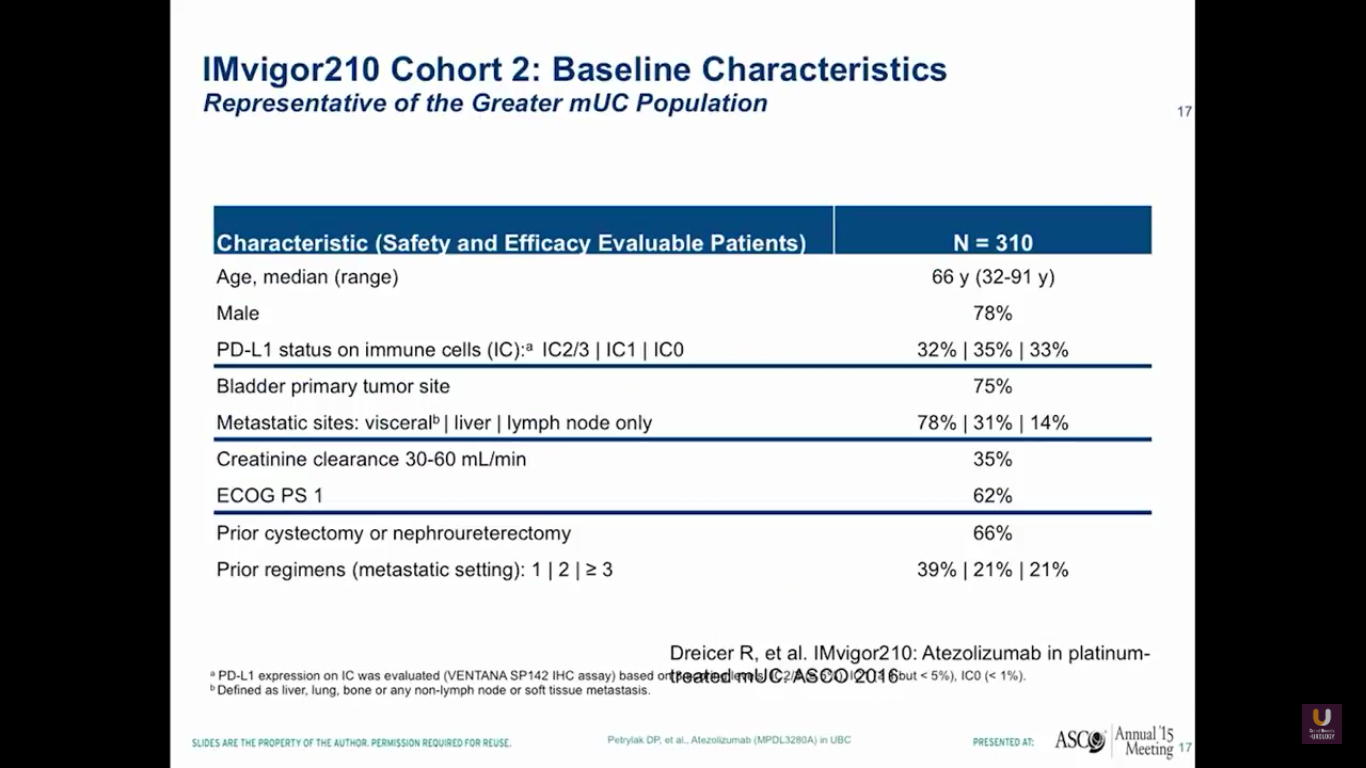

Overall, there were 310 platinum-experienced patients and 119 platinum-ineligible patients. The 310 platinum-experienced patients were a very similar group to the group we observed in the phase I trial.

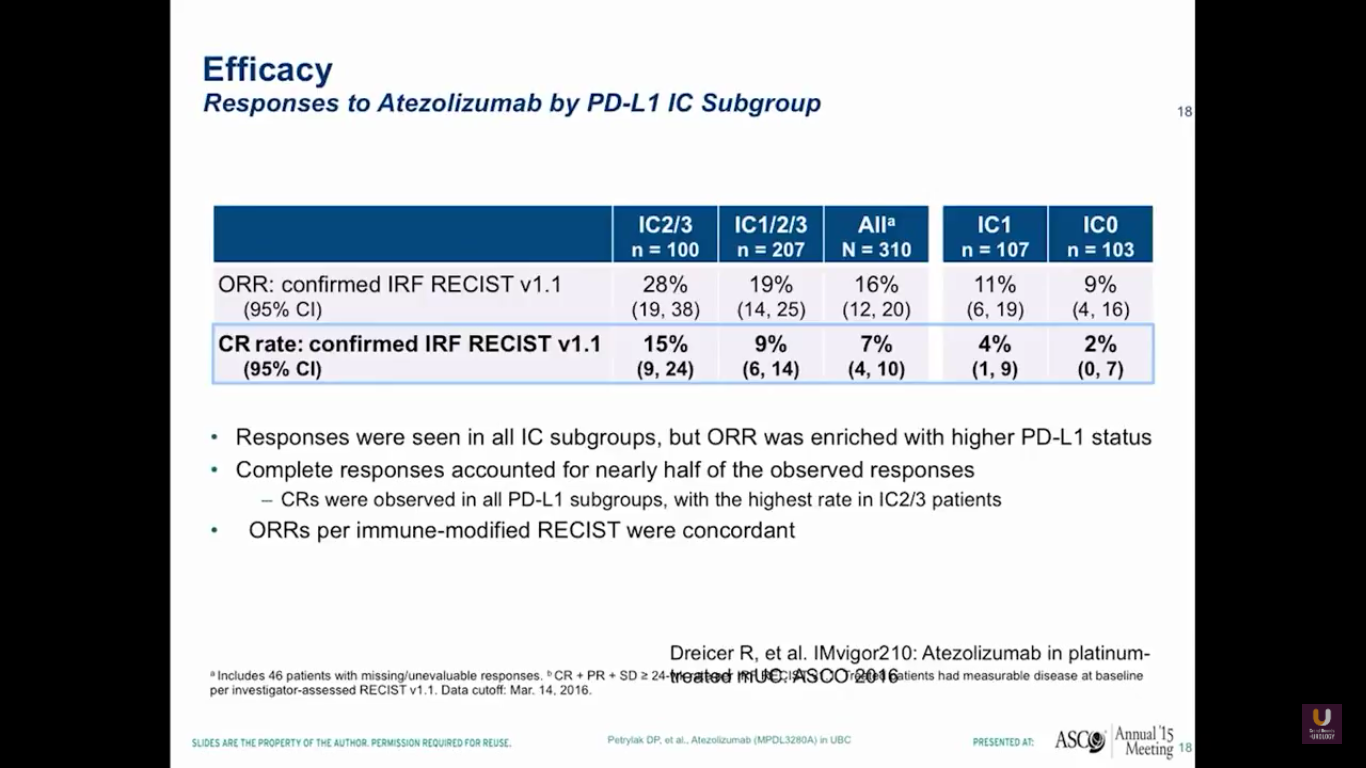

This data, of course, isn’t very mature. But, by looking at PD-L1 status in the immune cells, we see the same loose pattern of RECIST responses in both the group with high levels of expression and the group who did not express PDL-L1.

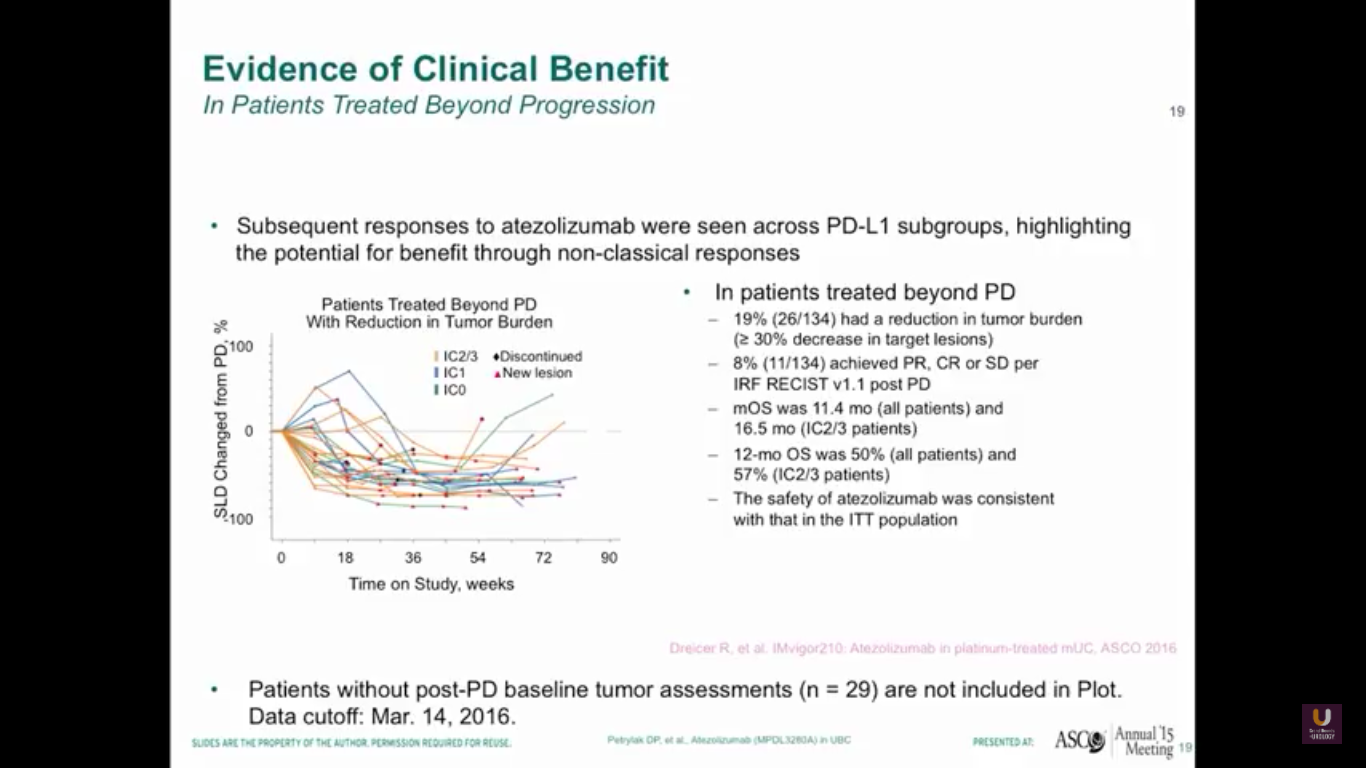

As oncologists and urologists, we have to keep in mind that response criteria for checkpoint inhibitors is different than the response criteria we have for standard chemotherapy.

Why? Well, in our trial, immune cells may infiltrate the tumor cells, the lymph nodes, or the liver, so we treated patients if they were asymptomatic past progression. Therefore, 19% of patients entered into the study were eligible to be treated past progression, and we saw that we had responses in these patients. We rescanned them a month after and continued them past their initial progression. We have to be careful not to be tricked by something called pseudo progression with these patients. We have to make sure they are truly progressing overall.

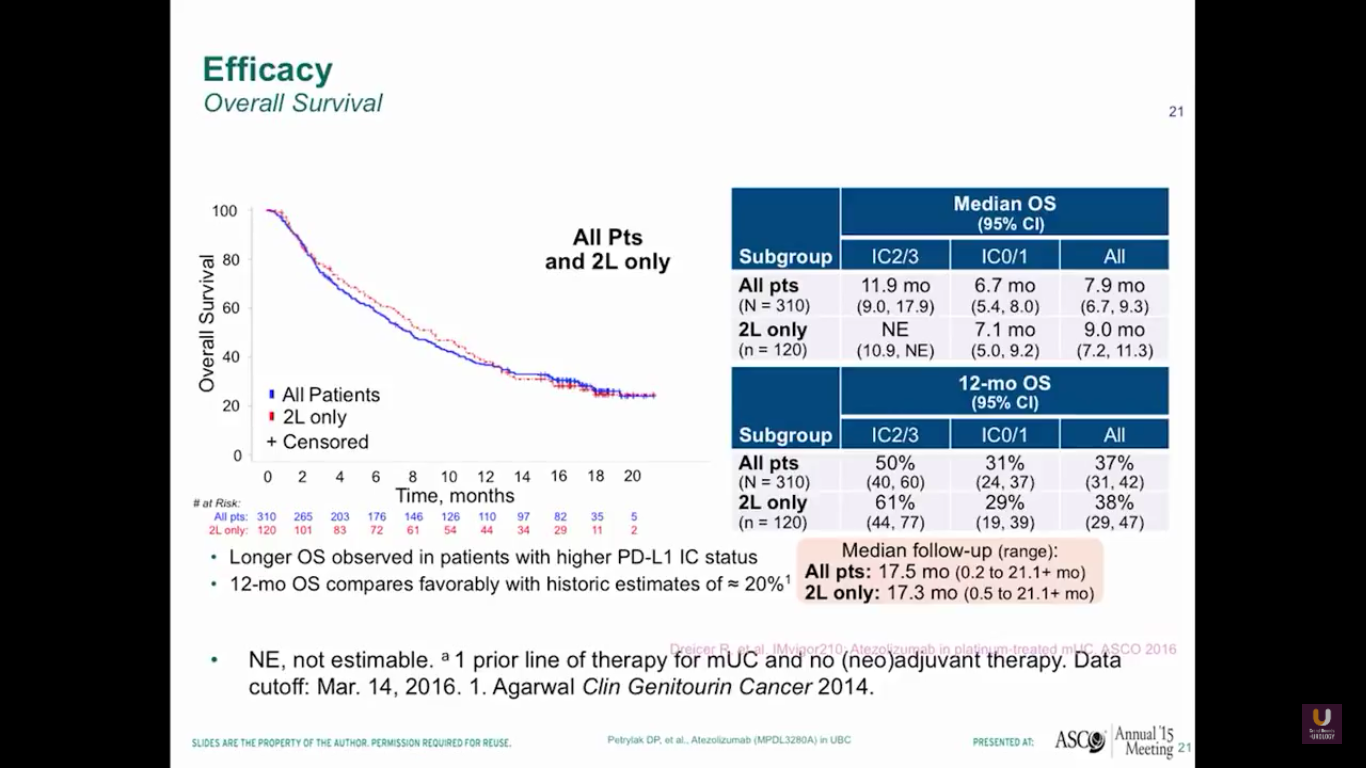

Here is the survival data from our trial. Again, this trial is not very mature. You can see that the 2/3s have a median 12 month survival rate, and all patients have an 8 month rate. 37% of all patients have a 12-month survival. We don’t see any difference in patterns between the all patients versus the second line only.

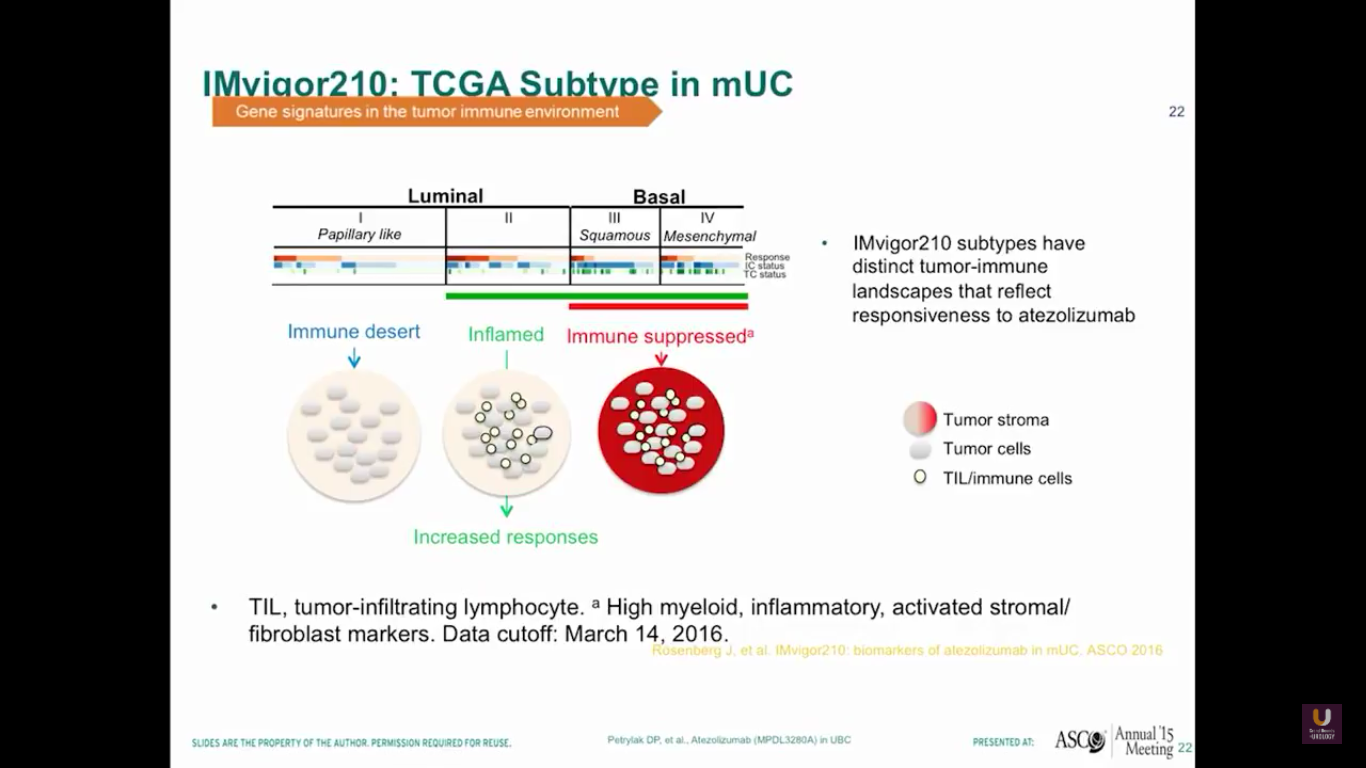

Now, let’s look at different types of bladder cancer histology. We have the luminal type, which can be considered to be the type 2s of the inflamed. The basal type is immune suppressed. Then, there is the papillary type, which is the immune desert. It seems that responses tend to occur in patients who have the luminal type 2 types in their histology.

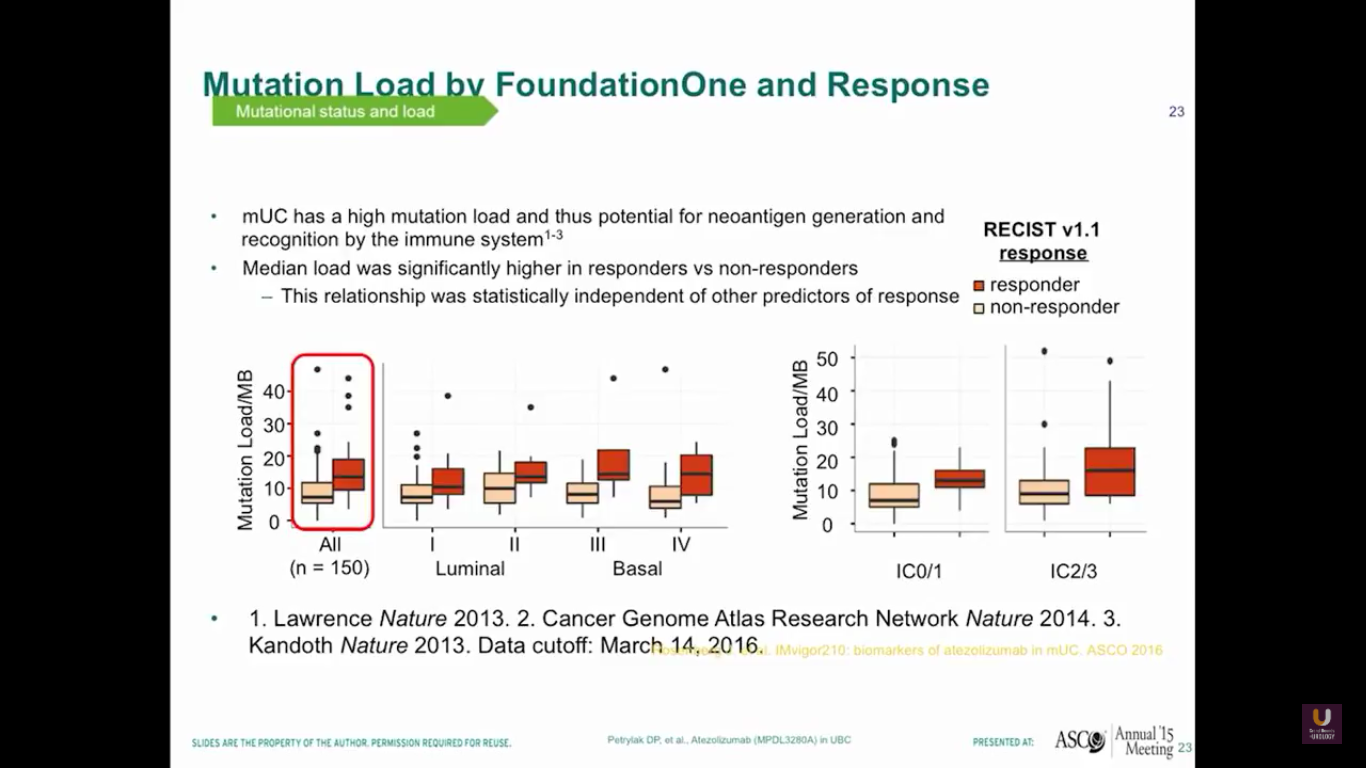

Also, if we plot out mutational loads in each individual patient, we’ll see that those patients with higher loads of mutation will do better and have a higher response rate. You can see the luminal type 2s separated in this diagram. Therefore, mUC has a potential for neoantigen generation and recognition by the immune system.

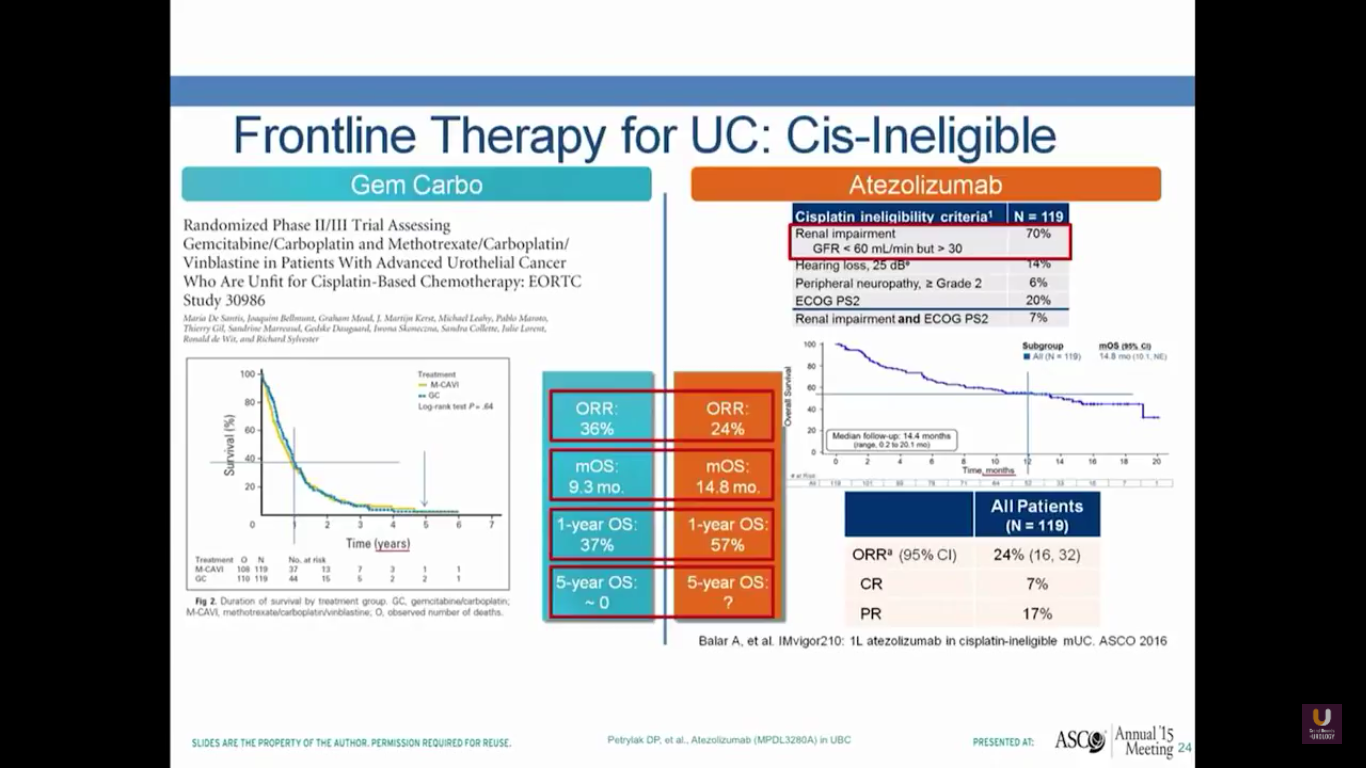

What about frontline therapy? Of course, if we move treatments up earlier, we expect a better response rate. On the left-hand portion of the slide, I’ve shown the de facto standard of care, which is gemcitabine and carboplatin. In the EORTC, they looked at this particular combination and compared it to a methotrexate-carboplatin-vinblastine combination. They found that this had a very similar survival, with objective response rates of 36%, median overall survival of 9.3 months, and a one-year overall survival of 37%, but no patients living 5 years.

In the cohort from this study, where platinum-ineligible patients who had not undergone prior chemotherapy received atezolizumab treatments, there was a 24% objective response rate, a median survival of 15 months, and a 57% overall one-year survival. But, the study is not mature enough for us to see a 5-year survival. This is comparable to what you see with carboplatin and gemcitabine. I would also argue it’s comparable to what you see with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Of course, we need randomized trials to prove that.

What are some of the other checkpoint inhibitors currently being evaluated?

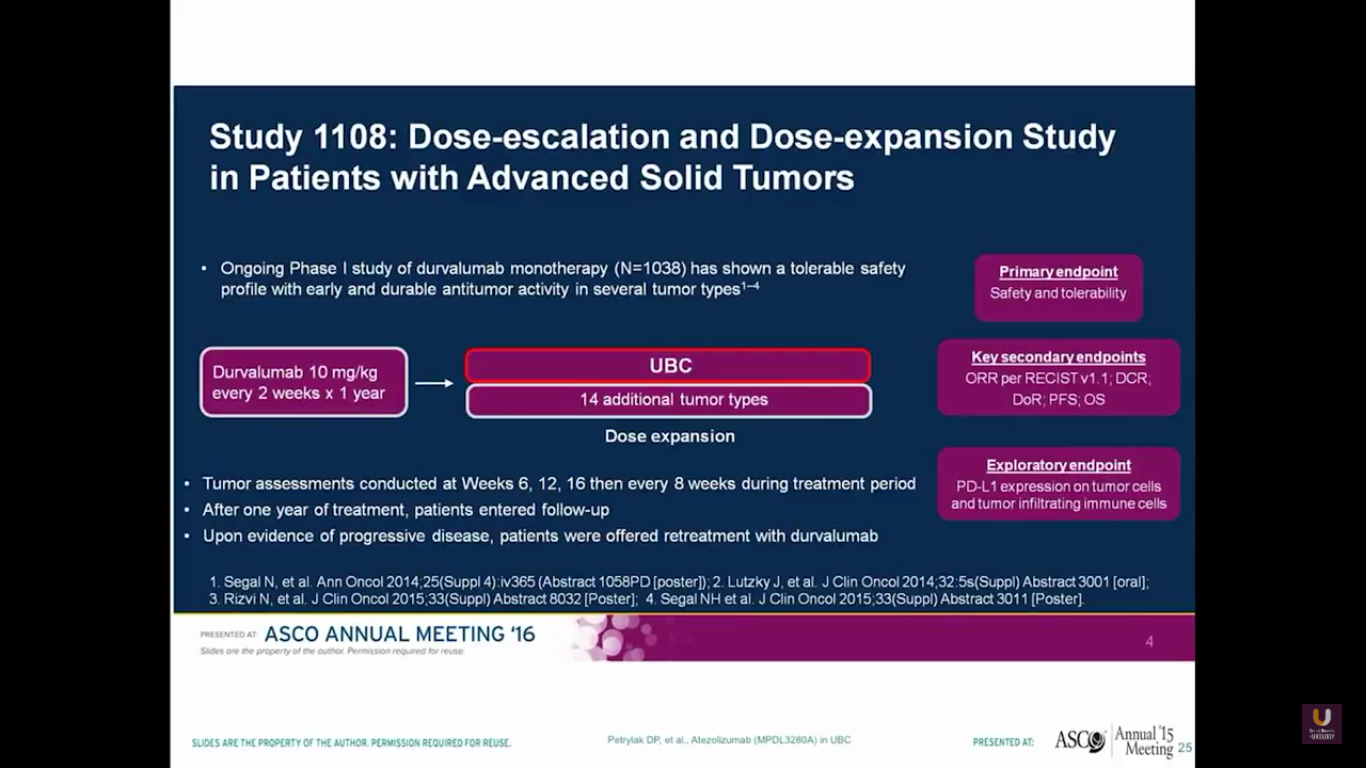

Durvalumab is a PD-L1 agent. It’s administered every other week. Patients receive this for a year.

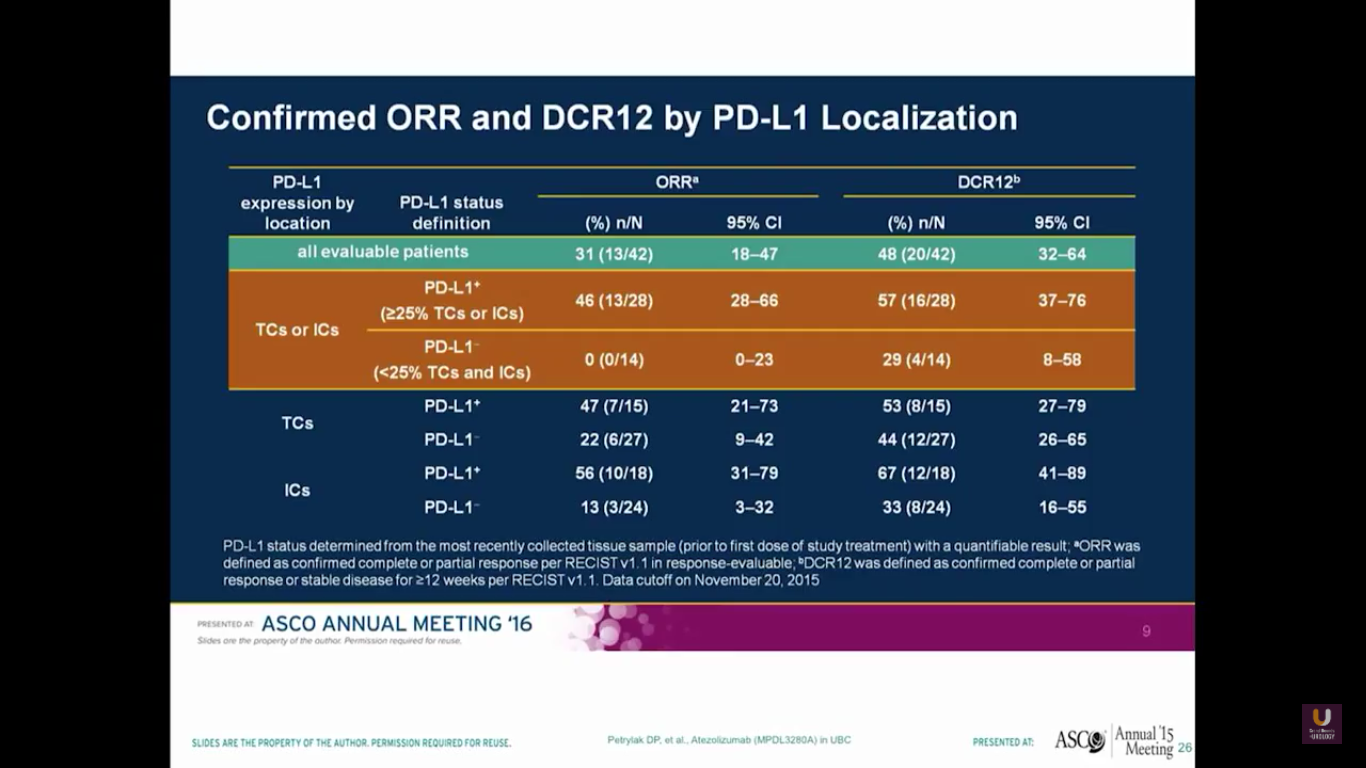

There was a urothelial bladder cohort from a phase I study. Their assays look at both the tumor cells and the immune cells. Keep in mind that this is a small sample size. Using their particular antibody, they found none of the 14 patients with expression in the tumor cells or the immune cells responded. But, out of the patients who had positivity, there was a higher response rate of 46%. They observed very similar side effects of inflammation, diarrhea, liver function abnormalities, as well as rash.

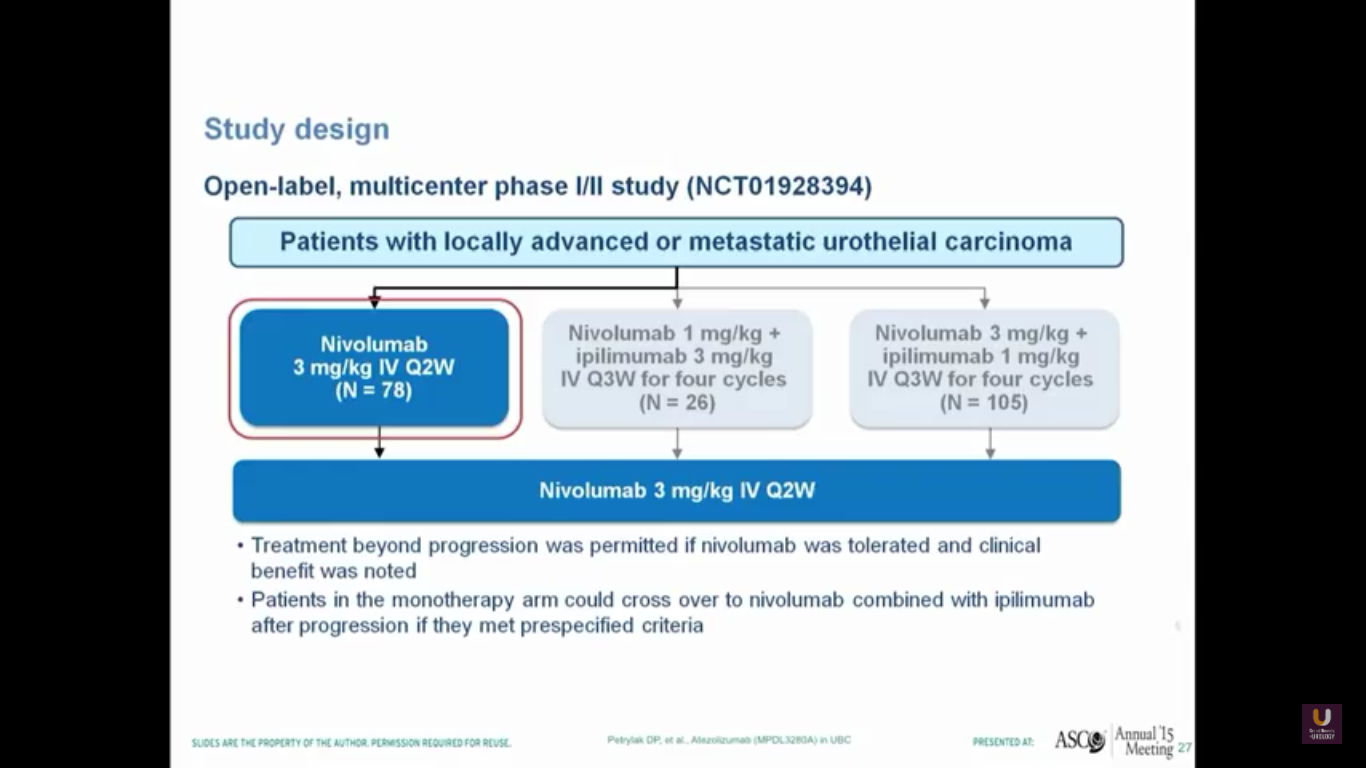

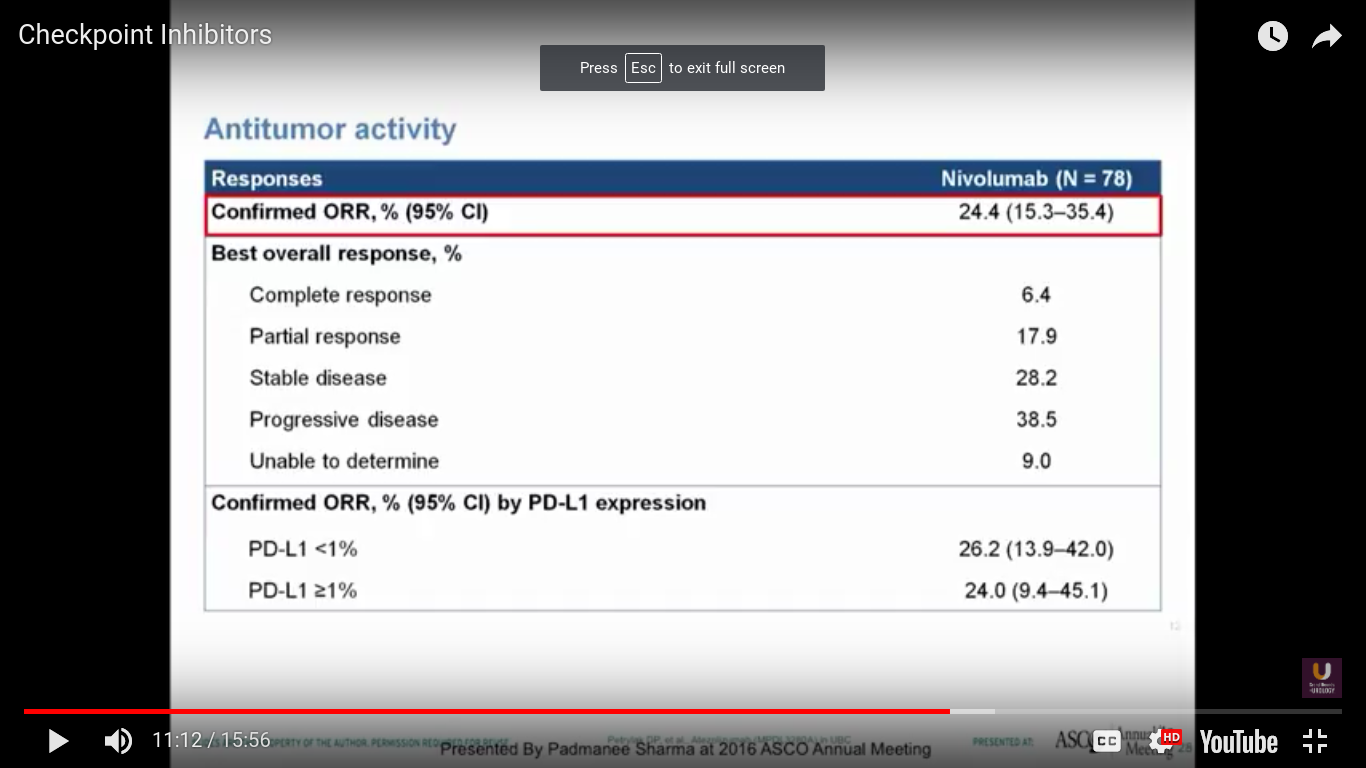

Nivolumab is approved for renal cell carcinoma as well as for lung cancer. This was evaluated in a single-arm trial and presented by Pam Sharma at ASCO last year.

In this trial, we see a 25% response rate, complete response rate of 6.4%, no correlation with PD-L1 expression, a progression-free survival of 2.78 months, and a median survival of 9.72 months. I think it is interesting that we don’t see a particularly great progression-free survival. Think back to PROVENGE a couple of years ago, when we didn’t see progression, but we did see a trend towards a better survival.

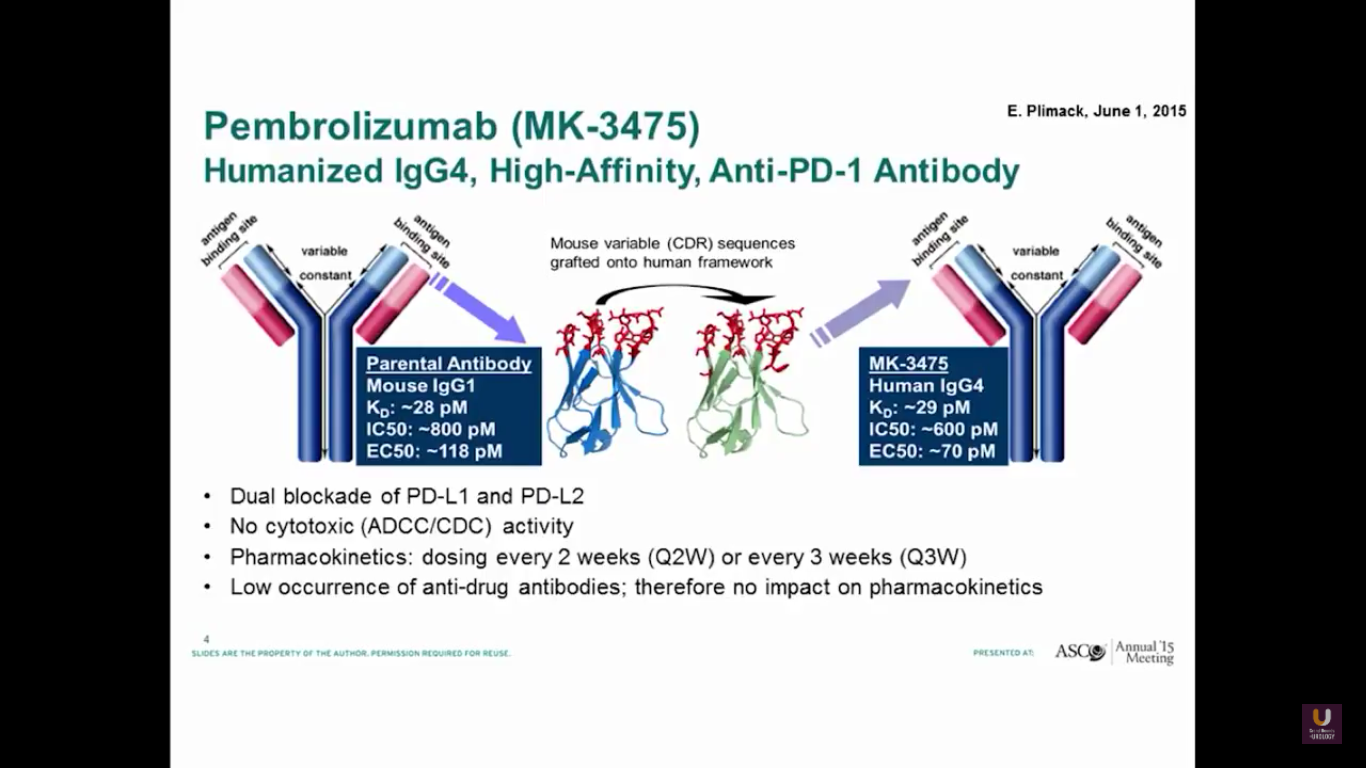

Pembrolizumab is a PD-1 antibody. It has a dual blockade of PD-L1 and PD-L2. It is approved for lung cancer. I believe it’s also recently been approved for head and neck cancer.

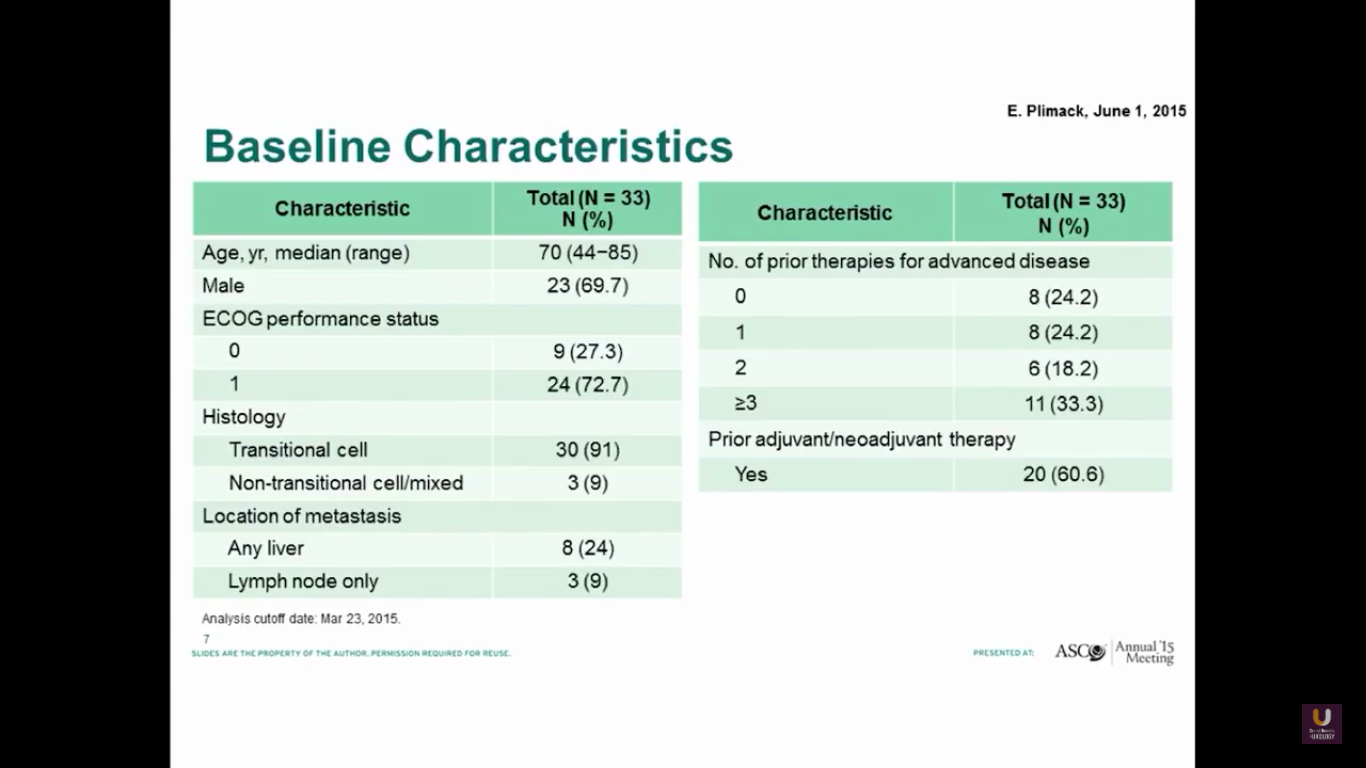

Betsy Plimack recently published this data in Lancet Oncology. She gave pembrolizumab to patients who had prior platinum-based therapy. As you can see, these patients are similar to our patients I discussed previously in this presentation.

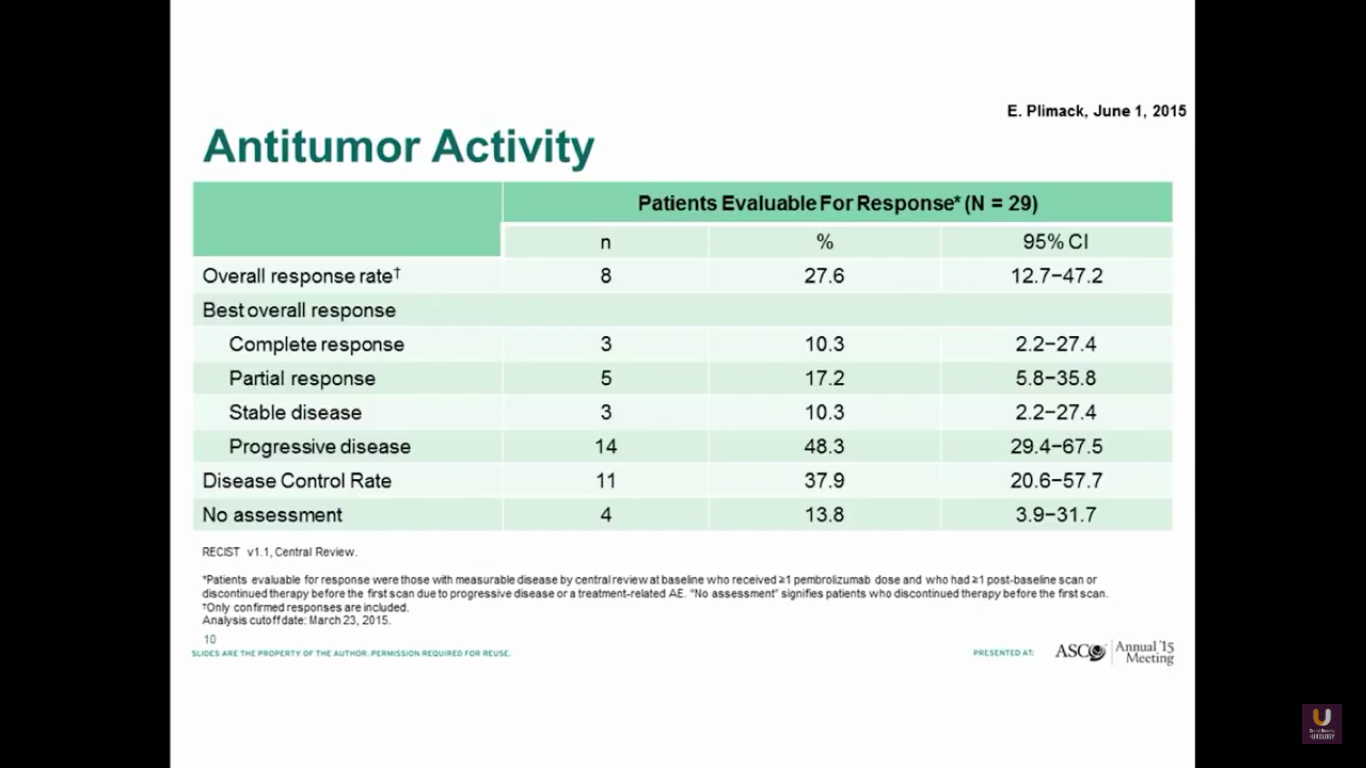

Both groups show a similar response rate of 27%.

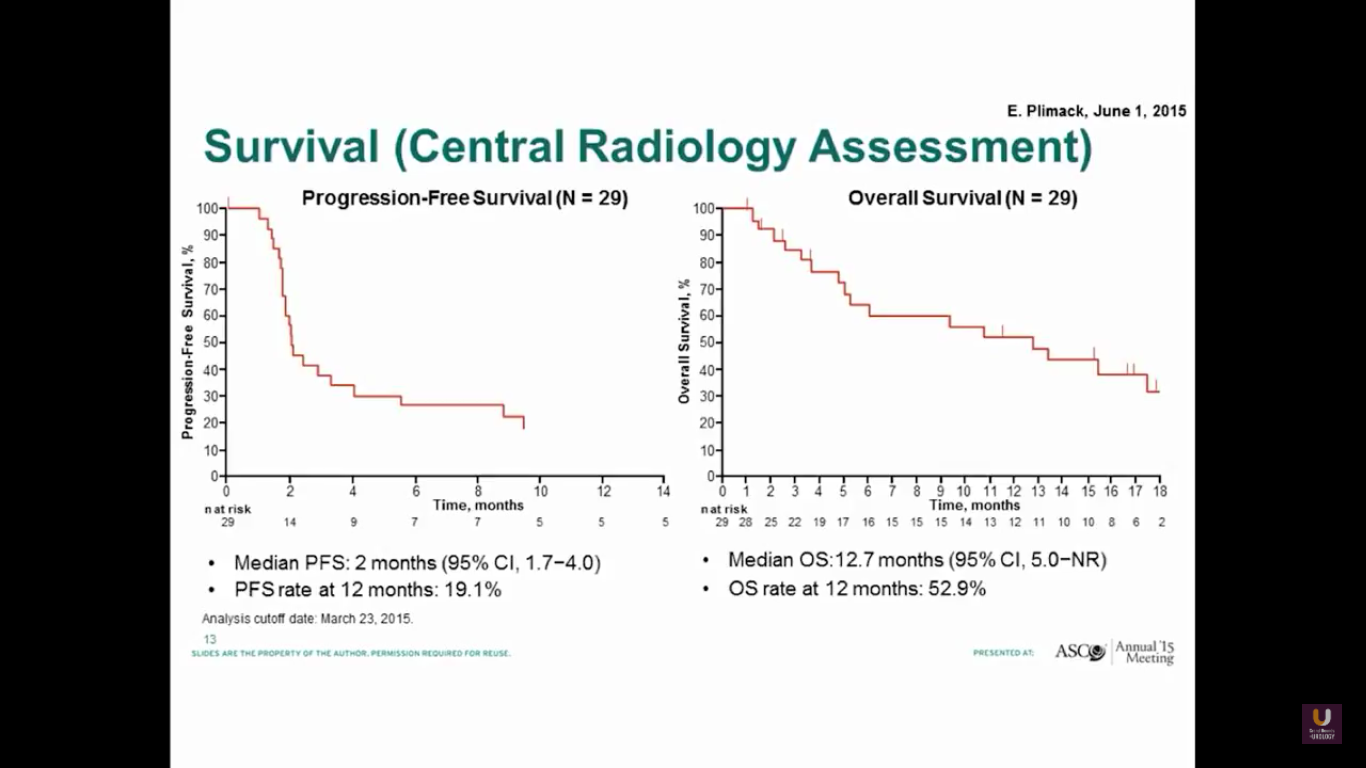

The progression-free survival is 2 months, which is not great. But, the overall survival is about 13 months.

What about randomized trials?

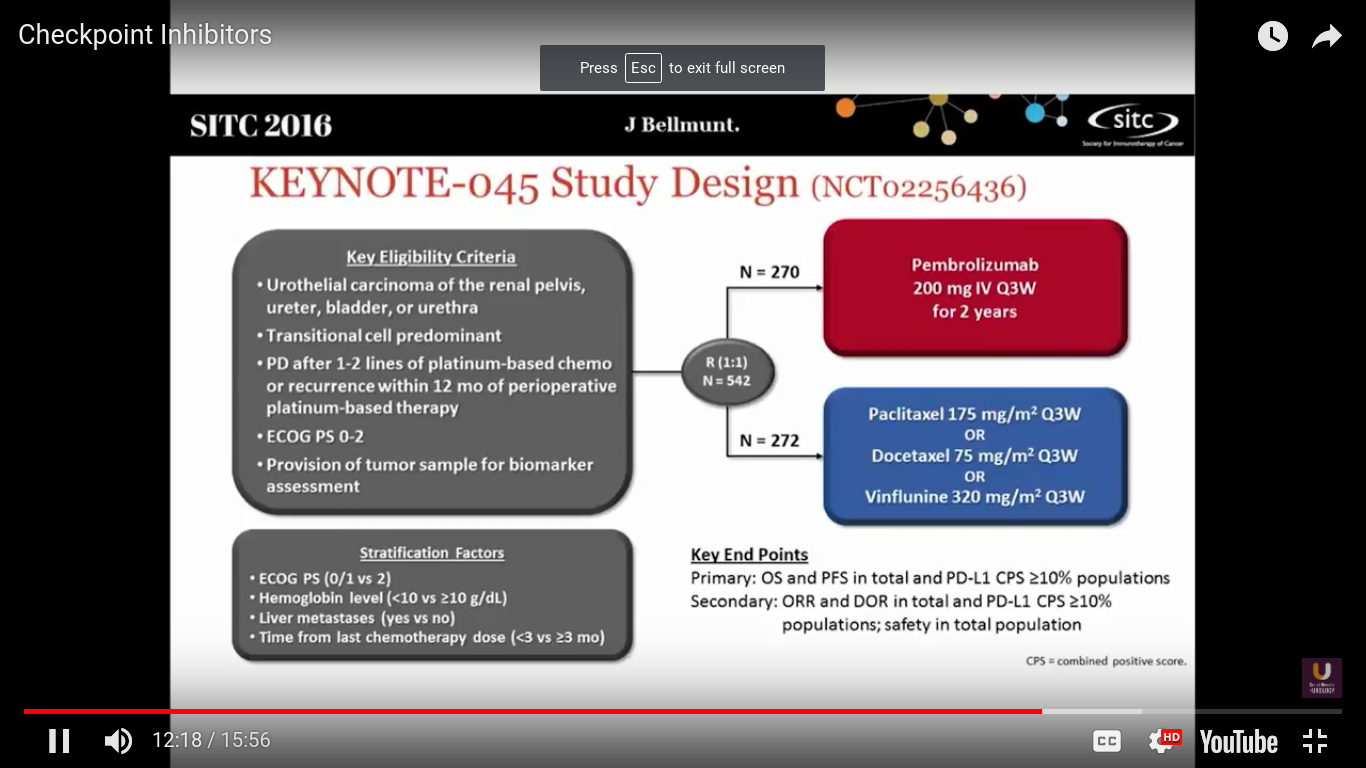

Well, this is the first randomized trial to be presented looking at checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic urothelial cancer. Joaquim Bellmunt was the PI on this study. This trial took patients who had at least 1-2 lines of platinum-based chemotherapy, or recurrence within 12 months after neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy. They were randomized to receive pembrolizumab every 3 weeks, or dealer’s choice chemotherapy. In Europe the standard of care is vinflunine. It is probably not any better than other chemotherapeutic agents.

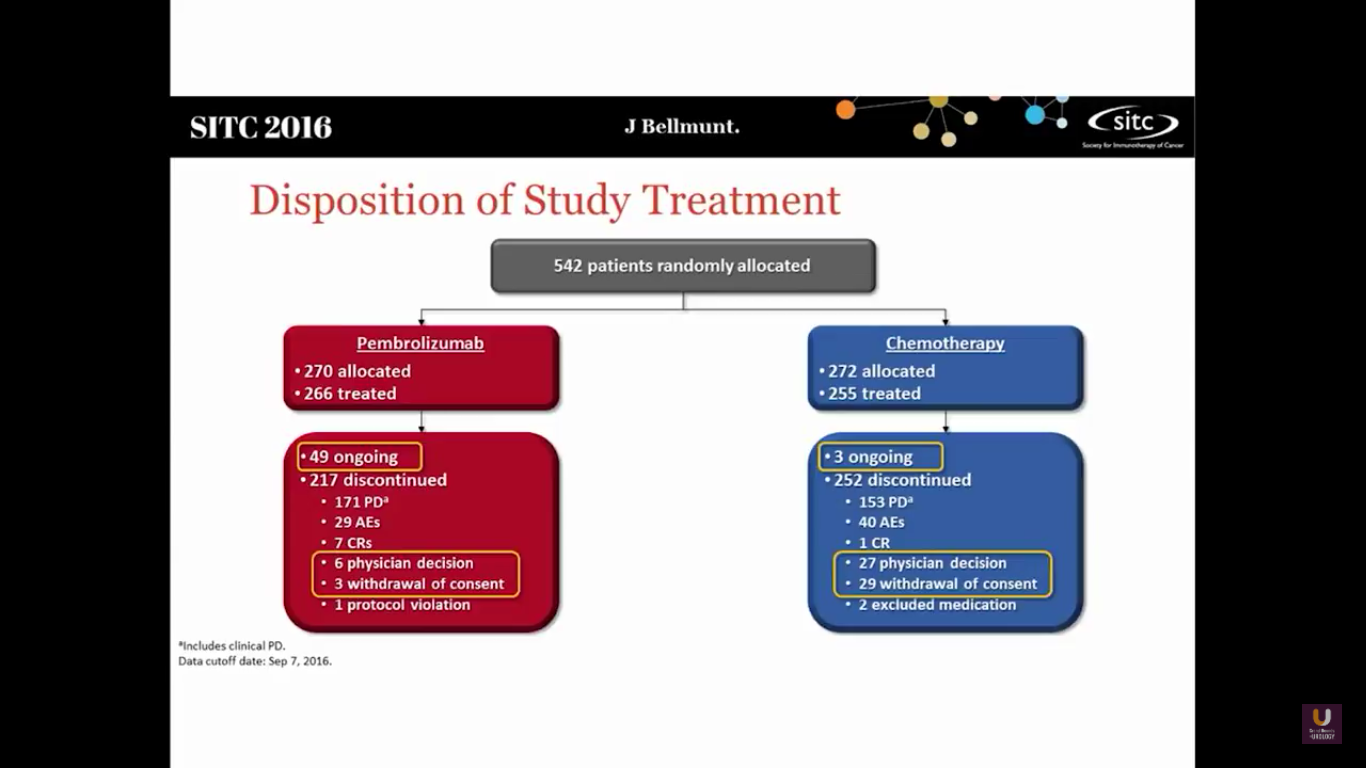

This study randomized 542 patients into both arms. There are still 49 ongoing patients in the Pembro trial and 3 in the chemotherapy arm.

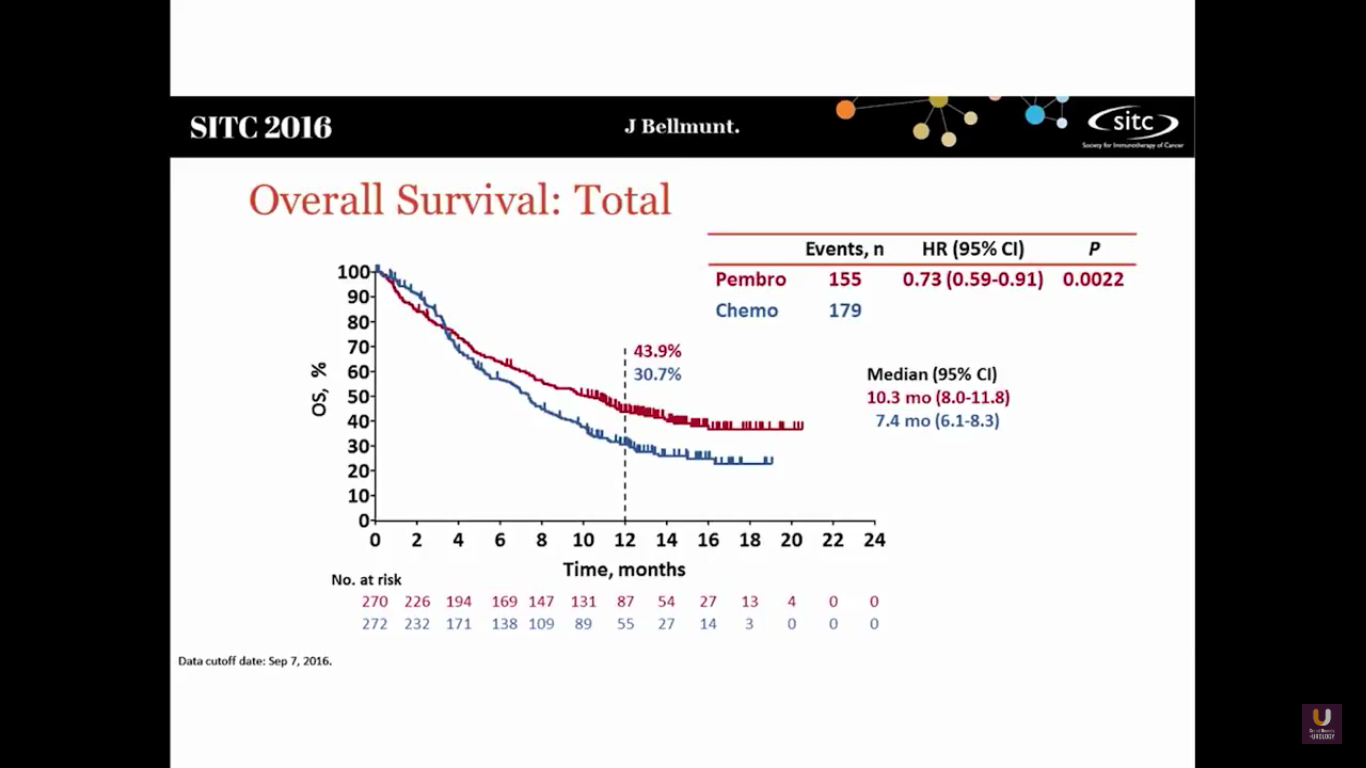

This shows that Pembro has a survival benefit. The hazard ratio is 0.73, with a median survival of 10.3 months, versus 7.3 months in the chemotherapy arm.

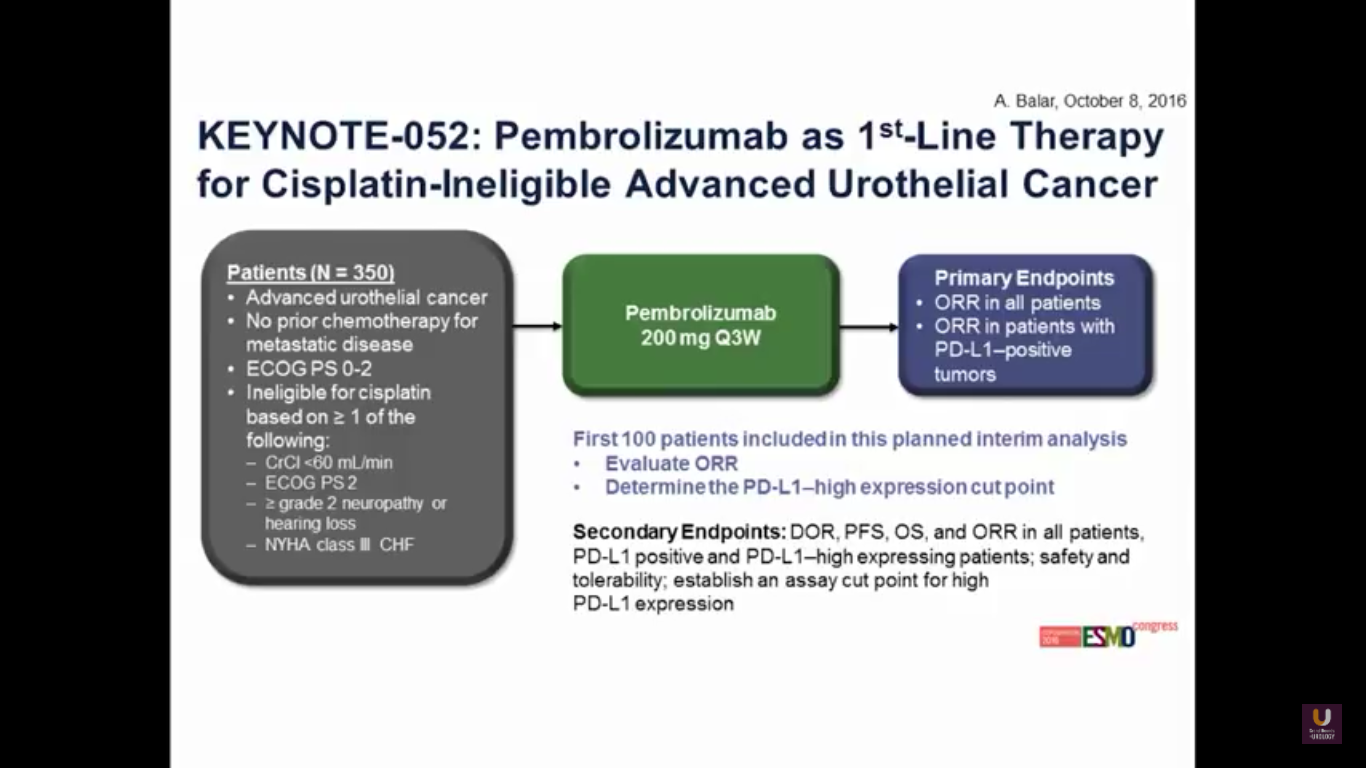

Now, what about moving pembrolizumab upfront in patients who are platinum ineligible?

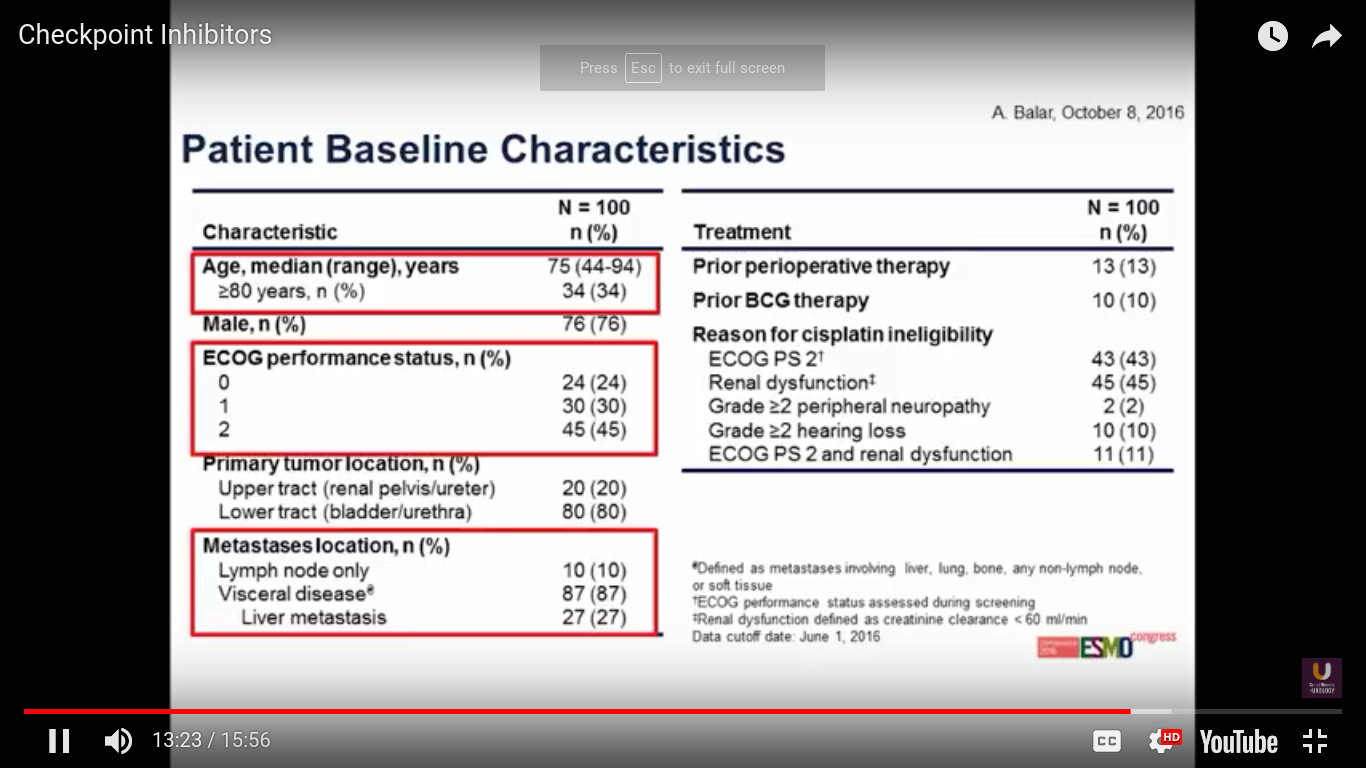

This was presented at ESMO this year. The trial has 100 patients overall. Predominantly, the patients have bladder cancer. 87% of patients have a visceral disease.

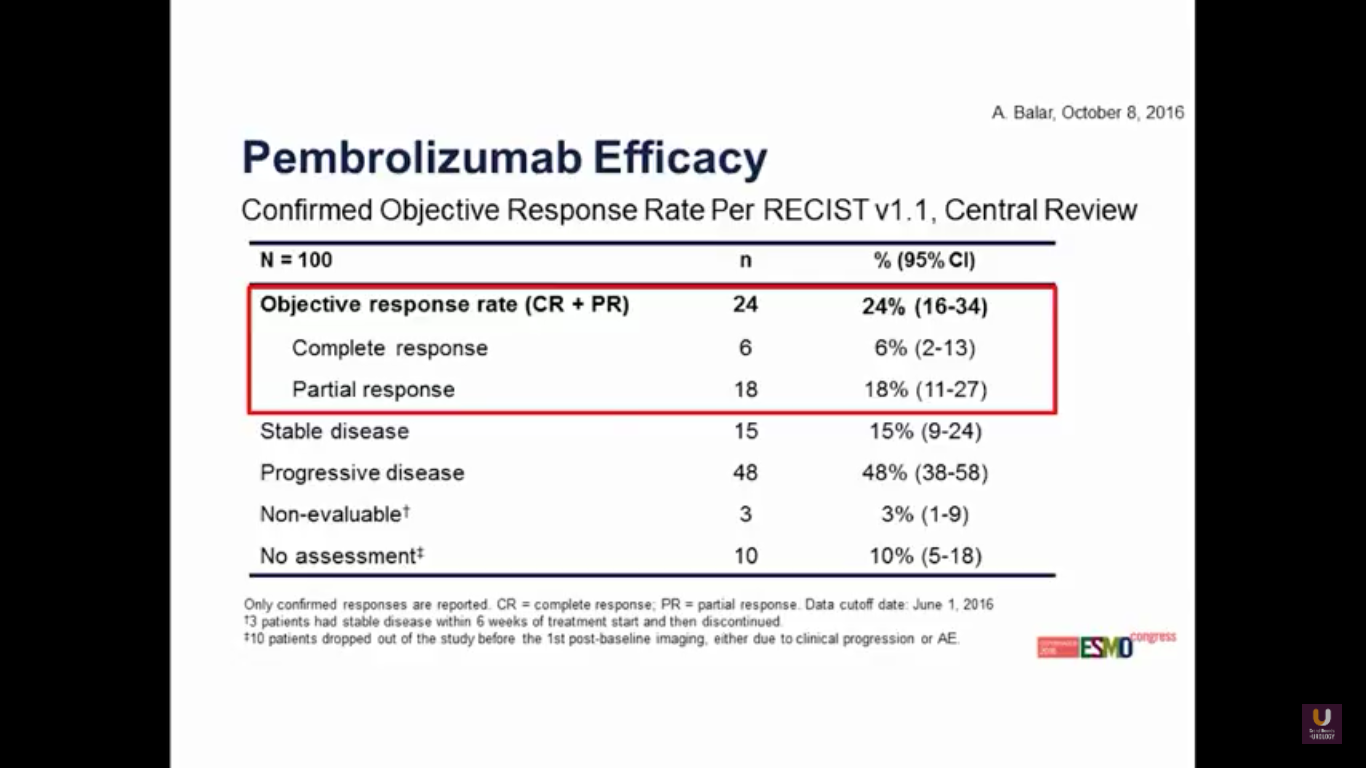

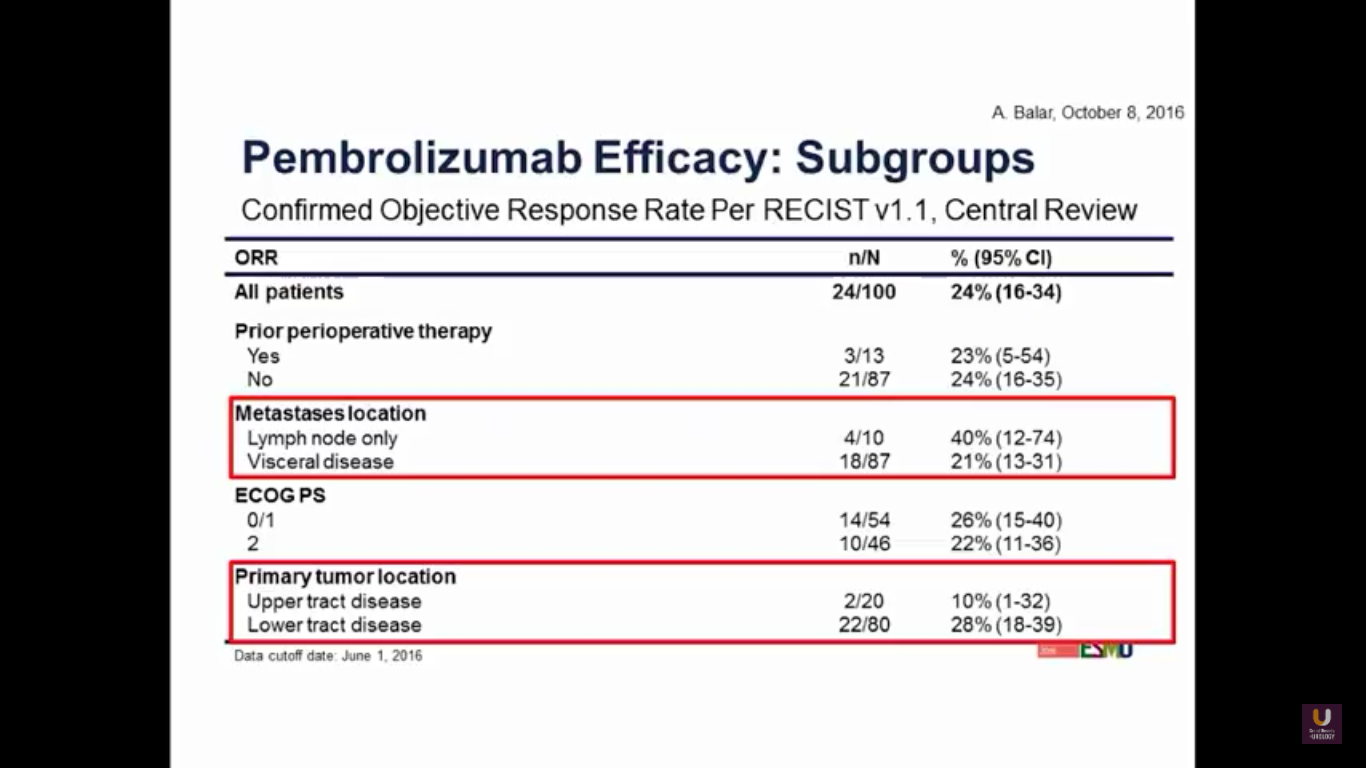

Again, we see that familiar 24% response rate, with 6% of patients having a complete response. So, we can track similar activity in agents across the board.

If we look at subgroups, we may observe better activity in the lower tract disease. But, with visceral disease, as we’ve seen consistently in the other trials, does tend to have a lower response rate.

There are a variety of studies moving upfront.

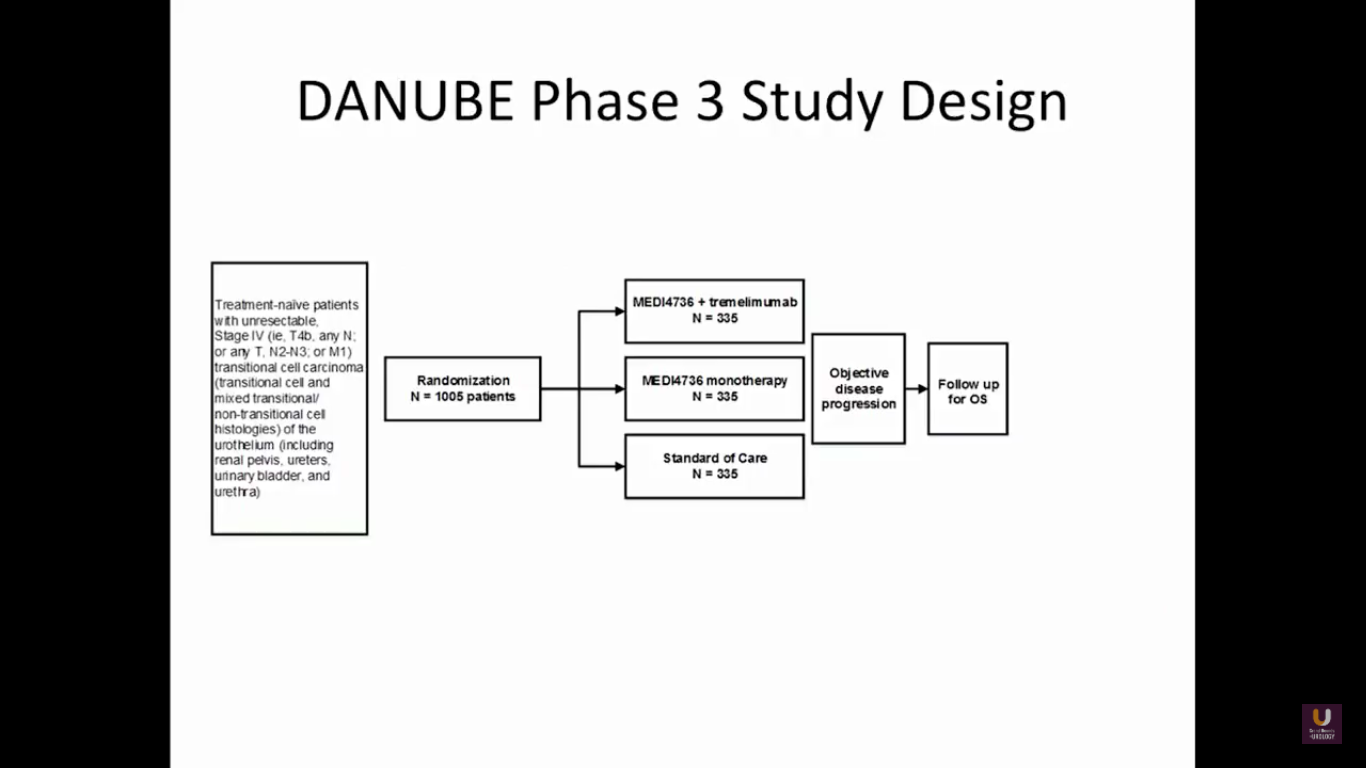

At this particular point, I’ll disclose that I’m on the steering committee for this trial. This is the DANUBE study. It is taking MEDI4726, which is an anti-PD-L1 inhibitor, and combines that with tremelimumab. It’s like giving ipi-nivo, a similar combination. We are comparing this to PD-L1 monotherapy and a standard chemotherapy in metastatic patients. This trial has closed in the United States, but is still actively accruing in Europe as front line.

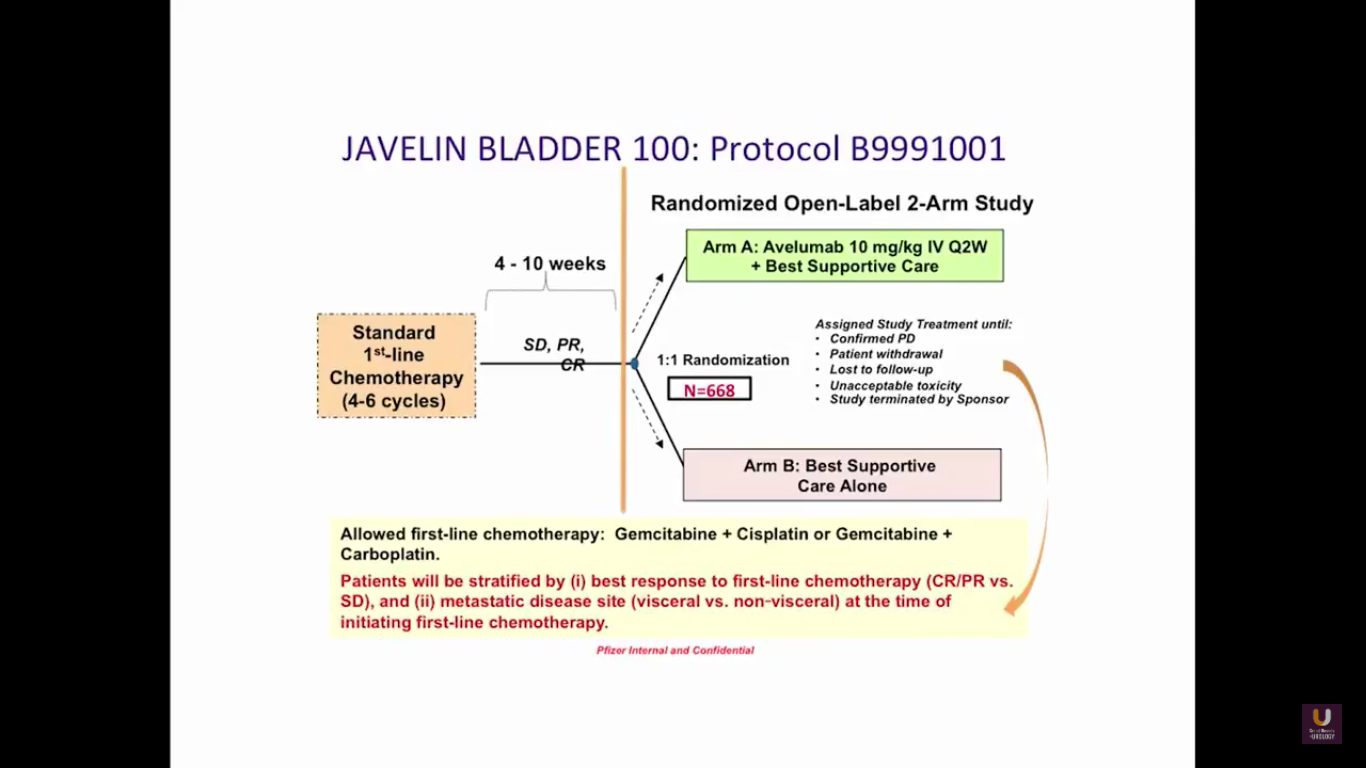

The JAVELIN trial is fairly interesting because it comes from the standpoint of a maintenance trial. Patients are receiving upfront chemotherapy for 4-6 cycles. If patients have a partial or complete response initially, they are randomized into either checkpoint inhibition therapy or observation. There are also trials being performed with atezolizumab and pembrolizumab upfront in bladder cancer.

In conclusion, checkpoint inhibition therapy demonstrates significant antitumor activity in cisplatin-treated metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Atezolizumab is FDA approved. I expect that Pembro to be approved at some point this year, but I’m not sure when. Also, Genentech has filed for frontline use in patients who are platinum ineligible. I think we really need to understand a more standardized way of looking at these markers. They do not tell us anything at this particular point, and should not be used to determine whether a patient goes on this treatment.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Daniel P. Petrylak, MD, is currently Director of Genitourinary Oncology, Professor of Medicine and Urology, Co-Leader of Cancer Signaling Networks, and Co-Director of the Signal Transduction Program at Yale University Cancer Center in New Haven, Connecticut. He is a recognized international leader in the urology field. He earned his MD at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland Ohio. He then went on to complete his Internal Medicine Residency at Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Jacobi Medical Center in the Bronx, and his fellowship at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Dr. Petrylak has served as principal investigator (PI) or co-PI on several SWOG clinical trials for genitourinary cancers. Most notably, he served as the PI for a randomized trial that led to the FDA approval of docetaxel in hormone refractory prostate cancer. He also helped to design and served as PI for the SPARC trial, an international registration trial evaluating satraplatin as a second-line therapy for hormone refractory prostate cancer.

Dr. Petrylak served on the program committees for the annual meetings of the American Urological Association from 2003-2011, and for the American Society of Clinical Oncology from 1995-1997 and 2001-2003. He also has served as a committee member for the Devices and Immunologicals section of the FDA. He has published extensively in the New England Journal of Medicine, Journal of Clinical Oncology, Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Cancer Research, and Clinical Cancer Research.