Dr. Matt T. Rosenberg presented “Testosterone, the FDA, and CVD Risk Controversies” at the 26th Annual Perspectives in Urology: Point-Counterpoint, November 10, 2017 in Scottsdale, AZ

How to cite: Terlecki, Ryan P. “Prostate Physiology: The Most Diseased Organ in the Male Body” November 10, 2017. Accessed Dec 2024. https://dev.grandroundsinurology.com/prostate-physiology-diseased-organ

Summary:

Dr. Matt T. Rosenberg, MD, argues both sides of the testosterone therapy controversy. He explains how supplementing testosterone in men with testosterone deficiency can be beneficial, but also risky from a cardiovascular standpoint.

Testosterone Therapy, the FDA, and CVD Risk Controversies

Edited Transcript:

The reality is, nobody likes to give a lecture on testosterone because it is insanely controversial.

Last year, I gave a talk in the point-counterpoint portion of this conference about the testosterone issues. I took the anti-testosterone side. It was hard because this is so controversial, and you can argue for either side. When we were setting up the agenda for this talk, Dave called me and a good friend of mine, Marty Miner, who’s one of the best internal medicine docs dealing with testosterone in the country. He asked me to help out because he’s having shoulder surgery. I had to really make an effort to learn as much as I could about the controversies.

A good speaker will tell you the conclusion to the controversy at the end of the talk. But, I don’t have a great answer. What I can show you is the data. I can show you the controversies out there.

Let’s start at the base level. What is testosterone deficiency?

It’s a well-established medical condition, no surprise. It is confirmed by low serum concentrations of T. It negatively impacts male sexuality, general health, and quality of life.

We all know the symptoms of testosterone deficiency (TD). There are libido problems, erectile dysfunction, decreased energy, depressed mood, irritability, and decreased sense of well-being.

The populations at risk are patients with congestive failure, type 2 diabetes, obesity, COPD, HIV, or chronic opioid use. I want to emphasize the 6-point initiative to mitigate chronic opioid use. We are experiencing an opioid epidemic in the US. We’ve heard a lot about it in the news. We’re around the primary cause of opioid abuse. Opioids may not be in an urology setting, but they’re certainly going to be in a primary care setting.

There are various comorbidities associated with hypogonadism. Obesity, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, osteoporosis, asthma, and COPD have tremendous odds ratios.

What else do we know? We know as we get older, testosterone levels go down.

The question is, is that natural? Is it okay to happen? It probably is. What’s the reasoning for that? If we change it, if we interfere with it as providers, are we helping the patient or not? That has become the most important question.

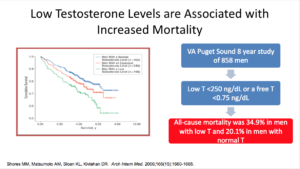

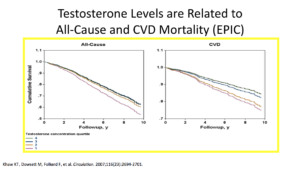

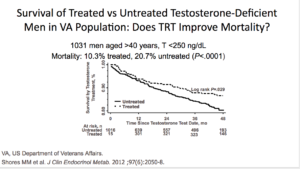

Let’s give ourselves a reality check. In reality, high testosterone levels are associated with decreased cardiovascular events. An old person with an elevated testosterone level is going to have decreased events. That’s good news. We also know that low testosterone levels are associated with increased cardiovascular events. We know this to be true in 2017.

We have to look at the articles published in 2017. One review piece that looked at 19 eligible articles looking at factors such as testosterone and atherosclerosis, stroke, myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and death from coronary heart disease or mortality. The articles showed evidence in the older population, as in people over 70, people with higher testosterone have decreased cardiovascular events.

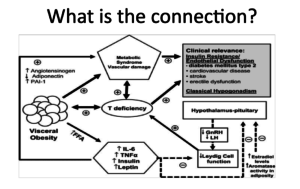

What is the connection? This is what we’re trying to figure out. I don’t think I’ve found anyone with a good answer, at least in my review. There are a lot of hypotheses out there. The root of any connections we can draw is in this diagram. Insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction increase your risk of diabetes. We know diabetes is associated with cardiovascular disease. Therefore, we see increased CVD, increased stroke, and erectile dysfunction. Nowadays, we know erectile dysfunction is a cardiovascular disease.

What is the connection? This is what we’re trying to figure out. I don’t think I’ve found anyone with a good answer, at least in my review. There are a lot of hypotheses out there. The root of any connections we can draw is in this diagram. Insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction increase your risk of diabetes. We know diabetes is associated with cardiovascular disease. Therefore, we see increased CVD, increased stroke, and erectile dysfunction. Nowadays, we know erectile dysfunction is a cardiovascular disease.

Why does testosterone spark controversy?

It’s for this reason. Testosterone comes with good news and bad news. We used to think that if you gave testosterone to an older male with a low testosterone, you would make him better. Because obviously, if he had low testosterone and a higher risk, we should reverse that.

However, after studies, we found the bad news. I want to start explaining the bad news by looking at the TOM study. It looked at what happened after giving elderly, frail patients testosterone. The population was made up of 209 male patients, aged greater than 65, with low testosterone levels. They were randomized to receive testosterone or a placebo. The testosterone gel was titrated from 50 to 150 mg/d.

The testosterone showed benefit. The patients were better. They were stronger, like the $6-million-dollar man.

The problem was safety. 23 men receiving testosterone reported cardiovascular adverse events, while only 5 men did in the placebo group. The study was terminated. It made the front page news- “This is bad. Testosterone is a bad thing to do.”

The TOM trial’s shortcomings was that the study itself wasn’t designed to assess adverse cardiovascular events. They didn’t look at the confounding effects that might result if these elderly males, who suddenly feel stronger, go to the gym. That would give them problems. The trial didn’t look at that. There was a lot of bias in the study.

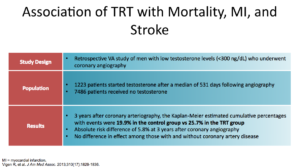

But, TOM is not the only study. It’s one of four. The second study is the Vigen study from JAMA in 2013. This study looked at what happens with testosterone therapy, mortality associated with MIs, and strokes with low levels.

It was a retrospective study, which is important to remember. They looked at men with low T and who had angiographies. They gave some of them testosterone and none to the other patients, then compared the two groups. The bottom line showed that the control group had a 19% risk a cardiovascular event, versus 25.7 in the testosterone group.

What does that mean? Well, it is bad news for testosterone.

In the initial statistical modeling, you can see that testosterone supplementation increased cardiovascular events after three years.

In the initial statistical modeling, you can see that testosterone supplementation increased cardiovascular events after three years.

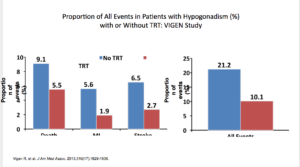

There were shortcomings with this trial, as well. The dosage, duration, and follow-up levels were not disclosed. There was no randomization or placebo. They used propensity score weighting as opposed to raw effect. When you looked at raw effect, it actually showed a benefit. The absolute risk of death, MI, or stroke was 21.2 % in the placebo versus 10 % in treatment.

The Vigen study excluded a lot of men. With all the controversy, societies went crazy. 29 societies retracted it. JAMA put an addendum on it. It’s very rare for them to reprimand a study in their own journal.

But again, when you look at it on the raw data, use of testosterone shows more promising numbers.

But again, when you look at it on the raw data, use of testosterone shows more promising numbers.

The third study was the Finkle study in the PLOS One January 2014 edition. They saw an increased risk of non-fatal MI following testosterone use.

Again, that’s what made front page news. The study design was a retrospective cohort study looking at patients with the risk of an acute, non-fatal MI in the 90 days following prescription. They looked at a lot of patients. They used 55,000 patients with testosterone versus 167,279 patients who were given PDE5.

It wasn’t a true comparison. But, they found that the men less than 65 years of age with prior heart histories were at heavy risk. If you were older, it didn’t matter if you had a heart history or not. Your risk was two-fold.

What were the shortcomings of this trial? It was a retrospective study without randomization or placebo control. The serum testosterone before and after treatment was unknown. The dosages were unknown. The CV risk factors were not discussed.

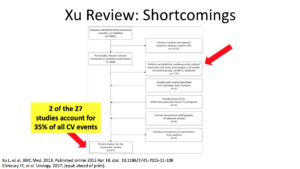

The fourth and final study essentially put nails in the coffin of testosterone. It was the Xu study. It was a meta-analysis of 27 placebo-controlled testosterone studies looking at men who received testosterone for more than 12 weeks. The results showed increased cardiovascular risks. They presented this as the global effect of testosterone.

The Xu study had a lot of shortcomings. Only two of the studies provided one-third of the total cardiovascular events. If you exclude those two studies, the results actually showed a benefit with testosterone.

I clipped this directly from the Xu’s paper. They said in their study that they excluded cardiovascular disease in the beginning. They shouldn’t have done that. They let 2 of 27 studies represent 35 % of all cardiovascular events.

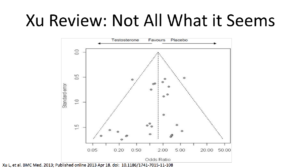

This shows the spread of the data. One side shows results that favors testosterone, and the other side shows results favoring placebo. Remember, this includes 27 studies. That doesn’t show me, visually, that testosterone is bad. It shows me that results are spread all over the place. It also tells me we probably need better studies.

shows the spread of the data. One side shows results that favors testosterone, and the other side shows results favoring placebo. Remember, this includes 27 studies. That doesn’t show me, visually, that testosterone is bad. It shows me that results are spread all over the place. It also tells me we probably need better studies.

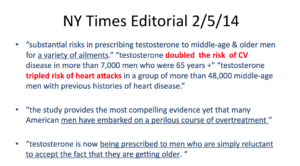

After the fourth study coming to the same conclusion, the lay press went crazy. This is a New York Times editorial from February of 2014. It says, “Testosterone doubled the risk of cardiovascular events. These studies provide compelling evidence that we’re over-treating. We shouldn’t be using testosterone, because we’re only doing it for guys that are reluctant to say they’re getting old.”

After the fourth study coming to the same conclusion, the lay press went crazy. This is a New York Times editorial from February of 2014. It says, “Testosterone doubled the risk of cardiovascular events. These studies provide compelling evidence that we’re over-treating. We shouldn’t be using testosterone, because we’re only doing it for guys that are reluctant to say they’re getting old.”

The FDA picked up on this in September of 2014. They came in and said, “You know what, we’re going to restrict this. We’re going to put limitations on testosterone use in companies. We’re going to clarify that evidence links testosterone therapy to danger, an increased risk of heart attack, stroke, and death.”

The FDA did admit that research was inconclusive. But they are taking the better part of valor and saying there’s a risk, and I agree with them. I agree that we don’t have a conclusive result. Ialso like the idea of a black box warning. Additionally, they advised the drug manufacturers to require better studies. I think we can all accept that.

Then they came out with this announcement in March of 2015: “FDA cautions about using testosterone products for low testosterone due to aging; requires labeling change to inform of possible increased risk of heart attack and stroke with use.” I’m actually okay with that. I’m okay that we have this discussion with patients. But, I’m really more okay with the idea that we just don’t know at this point, and we need better studies.

What is the good news? What is in the literature showing that testosterone is good?

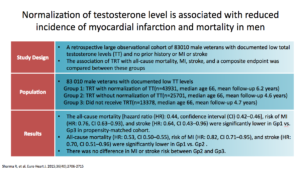

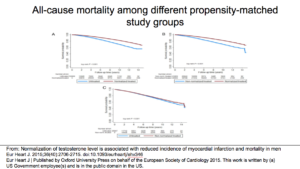

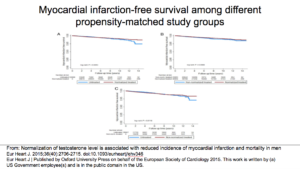

This is the Sharma study. They looked at a normalization of testosterone. It included a lot of people. They compared patients who had testosterone and got to a normal level (Group 1) against patients who had testosterone and never got to a normal level (Group 2) and patients who received no testosterone at all (Group 3).

The bottom line was that Group 1 did better than Groups 2 and 3. You see this in the results. Also, there was no difference in the risk of MI between Group 2 and Group 3.

This slide shows that, in treatment, normalization of testosterone had a better impact on all-cause mortality than what was observed in Groups 2 and 3.

This shows myocardial-free survival. Again, you see that Group 1 was better than Groups 2 and 3.

This shows myocardial-free survival. Again, you see that Group 1 was better than Groups 2 and 3.

With that, they included there was a reduction in all-cause mortality. The Sharma study had limitations, just like with the other studies I mentioned. It was observational. There was no control regarding when testosterone blood levels were drawn. In the paper, they admit they should’ve been doing the draws in the morning. They were doing the draws at any point of time in the day. That skews the results, because obviously, testosterone levels are higher in the morning. There was no randomization. They took limited data regarding who got therapy and why they did. There was no data about why some people never made therapeutic levels. Was the draw time wrong, causing them to achieve something with the testosterone when they weren’t? Were people not getting the full dose? There were a lot of concerns with that study. But, it does show something different from the other studies.

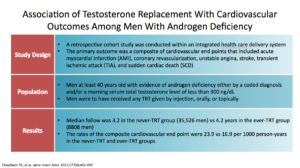

This was the Cheetham study, showing testosterone replacement with cardiovascular outcomes in men with androgen deficiency. It was a retrospective cohort study looking at primary outcomes of cardiovascular disease. They started with men were over the age of 40 who were given any sort of level of testosterone. The follow-up was 3.2 years in the never-T. The study compared groups who never got testosterone versus men who ever got it. When they say “ever,” they mean it didn’t matter how many doses you got. It only mattered if you were ever exposed to testosterone.

They found that men with androgen deficiency were associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular outcomes over 3.4 years. Again, the study had limitations. They didn’t use the standard endocrine guidelines for identification. It was an observational design. There were unmeasured confounding issues. Were healthier patients getting testosterone and sicker patients not? They couldn’t answer that question. The dose and duration were not controlled, because any dose of T at any time qualified a person to be in the ever testosterone study.

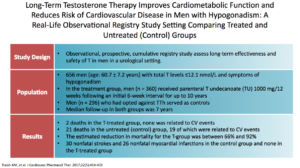

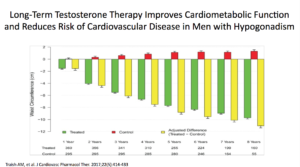

In the Traish study, an observational, prospective, cumulative-registry study, they looked at testosterone’s long-term effectiveness and safety in men in a urologic setting. This study looked at 656 men. There was a treatment group getting TU, testosterone undecanoate, and was followed for up to ten years. The control group consisted of 296 patients who opted against it.

Results showed a tremendous amount of benefit. There were 21 deaths in the untreated groups versus 2 in the testosterone group. Across the board, all parameters of cardiovascular disease improved. The estimated reduction in mortality, for the testosterone group, was between 66% and 92%.

In the untreated group, there were 30 non-fatal strokes, 26 non-fatal MIs. None of this happened in the T group. When you look at this paper, testosterone seems amazing. The data for the benefits of testosterone is unbelievable.

Waist circumferences were markedly improved. We know that if we can get our patients with cardiometabolic disease to lose weight, they’re going to do better. We can actually shift them out of cardiometabolic disease.

Therefore, they concluded that was TU was phenomenal. It worked very, very well. It improved all parameters, including the cardiometabolic, the risk of CVD events, the size, and the girth. Mortality-related CV disease saw a significant reduction in the testosterone group.

Of course, as with all the studies we’ve talked about, this study had limitations. The details show the study was not designed to address testosterone mortality. There was no acknowledgement of prior cardiovascular events. It was not randomized. There was also no monitoring of concomitant meds. I think the key limitation was that a single urologist ran this study. He was in one clinic in Germany.

Also, when I read into editorials on the paper, there was a significant selection bias because patients had to pay for their own testosterone. If you couldn’t afford it, you weren’t going to take it. Lower income people didn’t buy it. That may have been a source for some of the effects. We know higher income people tend to be healthier.

Still, these were very, very promising results for TU. It was a well-thought-out, well-written study. But, you have to take it with a grain of salt. It was from a single urologist. We need to conduct this text with a larger population in order to have more conclusive results.

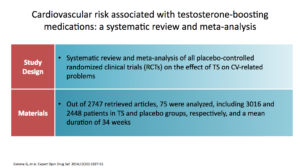

The Corona study was a systematic review and meta-analysis of all controlled clinical trials on the effect of testosterone supplementation on cardiovascular disease. Seventy-five studies were analyzed out of over 2,700.

They found that testosterone replacement was not related to cardiovascular risk, even when composite or single adverse events were considered. It seemed protective. The data did not support a causal role between testosterone supplementation and cardiovascular disease, which was was good. They concluded that the data that supports that hypogonadal men being treated with testosterone do better in terms of their cardiometabolic profile, as in reducing body fat and increasing lean muscle mass, which are precursors to CV. Certainly, we know those factors are precursors to CV from primary care experience.

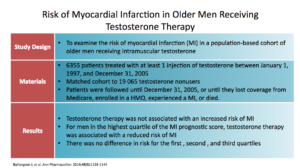

This study, the Baillargeon study, looked at myocardial infarction in a population-based cohort of older men getting IM testosterone. There were 6,300 men treated with at least 1 injection. It was a matched cohort to 19,000 men. Patients were treated and followed for 8 years.

The results show that testosterone therapy was not associated with increased MI. Interestingly, men with the highest risk for MI were the ones that did best. They had the highest reduction in MI. There was no difference in risk in the first, second, or third quartile. So, the biggest risk reduction was in the fourth quartile. That’s interesting. It did no harm to anybody. If you were at the highest risk, you did better.

They concluded IM testosterone was moderately protective against. Again, this test had limitations. Information from outcomes and risk factors came from diagnostic codes, which are questionable accurate. Medicare coding provided no data on other formulations. There was no assessment of comorbid states and other medications. They didn’t know if you happened to be on a statin, for example. There was no baseline information. It was a retrospective study, which obviously could have selection bias.

If testosterone affects cardiac disease one way or another, then what about the precursors to cardiac disease?

As your coronary vessels become blocked, you have more risk. That’s the precursor. You can’t have a heart attack without blocking the vessels.

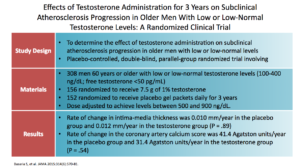

In the Basaria’s study, they looked the effect of testosterone administration on subclinical CAD progression in older men with lower, near-normal levels. They had a placebo control, totalling 800 men, who were randomized to receive testosterone or not. They found that intimal thickness was not significantly changed.

They concluded there was no difference in coronary artery calcium score rates of change. The precursors for cardiac disease weren’t there. If testosterone truly causes cardiac events, they did not see it.

This study’s limitations were that one, they didn’t see the improvements we would normally see with testosterone administration – sexual desire, erectile function, overall sexual score. That makes your eyebrows raise a little bit. Secondly, since the test was only powered to look at CAD progression, or atherosclerotic progression, you can’t establish this as a benefit of cardiovascular risk. Although, we would assume that if the occlusion wasn’t getting worse, it would be better or at least the same.

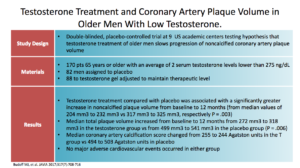

The Budoff study was a counter study to that. It was published just this year, in 2017. This was a double-blinded placebo-controlled study, at nine US academic centers, looking at testosterone replacement in older men and weather or not it slows the progression of coronary artery plaque volume. You see they had 170 men split 82:88 to receive either a placebo or gel.

They found that mean total plaque volume increased in the with testosterone. They did find that. The mean coronary artery calcification score decreased in the T group, but increased in the placebo group. There were no major cardiovascular events in either group, but that’s not what they were looking at.

They concluded that older, symptomatic, hypogonadal men treated with testosterone gel for a year had a significantly greater increase in CAD, or coronary artery non-calcified plaque volume. That makes us raise our eyebrows again. Also, they admitted we needed larger studies to understand the clinical implications. That directly counters Basaria’s study.

As per the limitations – this was not randomized. There were different baseline groups depending on baseline plaque volume. The baseline for placebo was at a different than the treatment group’s baseline. Their prognostic studies on non-calcified plaque volume were non-existent. Did this simply show progression of bad plaque versus good plaque? Some plaques are better than others. They can’t answer that question.

So, what do we know about testosterone at this point? What do we know in 2017?

Honestly, I can only tell you that there are three sides to every story. There’s my side, there’s your side, and there’s the truth. The reality of it is – I don’t know if we know the truth right now. It really depends on the way you look at it.

If we don’t know the truth, then we, in the medical community, are at risk. We see article like this cropping up in the lay press. We see lawsuits on testosterone on CNN and Fox News. This is because we don’t know the absolute truth.

Now, as providers, what do we do?

Immagine a horse – the horse being testosterone. How do we want to look at it?

Do we want to look at the head of the horse? That’s one aspect of testosterone. Do we want to look at the side of the horse? Do we want to look at the rear end of the horse? I don’t really know.

What are my conclusions from what I’ve learned?

For me, it doesn’t change how I practice. I’ve been using testosterone for years. I’m going to continue using testosterone.

However, I’m going to keep track of the literature. That helps me when I have to deal with legal issues. I have to be vigilant and pick the right patient. Testosterone is not for everybody. It is only for the right patient.

How do I know who is the right patient?

I have to assess the cardiac risk. If you come into my office and you’ve had a heart attack, chances are I’m not going to give you testosterone. If I think you might have any sort of risk, I’ll talk to the cardiologist and maybe send you in for a cardiac evaluation. I would also be wary about giving patient testosterone if they’ve been treated for prostate cancer. We know that is possible nowadays, but I’m still going to have a discussion with you first. If I’m going to consider it for you or any patient, I’m going to discuss the risks and benefits.

If a patient insists on it, maybe I will have him sign a waiver saying he understands the risks. Also, as urologists, you want to discuss this with primary care. Don’t let primary care give out testosterone without talking to you. That’s a bad idea.

The key is communication, as Dr. Cookson mentioned before. And finally, whenever you use testosterone, make sure to document everything you do and see so we’ll have more facts moving forward.

Testosterone is like a moving target. I don’t know what its future holds. Thank you.

Questions from the Audience:

~“My question to you is, can a man like myself, by losing 20 pounds, increase his serum testosterone level just with weight loss? Is serum testosterone really just a marker for your overall health?”

Dr. Rosenberg’s Answer: That’s a really, really good question. Let’s say I was seeing you in the clinic. What would I tell you? My first answer would be yes, you should lose weight. We know that testosterone gets the aromatase enzymes from the adipose tissue and then turns into estrogen. In that way, I can improve your testosterone levels and the effect it has on you by getting you to lose weight. The counter to that idea is that – how do I start that process? Do I give you testosterone to make you more energetic and able to go to the gym, or do I encourage you to go to the gym to raise your testosterone? For safety issues, I would tell you to go to the gym first. We’ll see what that does for you and monitor your progress. If I see that you have symptoms of low T, I might treat you for that. I do think T is a marker of health issues, but at the same time, I think a lack of it causes other health issues. It’s a balance. Dave might have more insight on this.

~“How many urologists tell their low testosterone patients to go to the gym?”

Dr. Rosenberg’s Answer: In primary care, we tell them all to go to the gym. In fact, if I was smart, I’d own a gym.

With that, I should wrap up this panel so Dave doesn’t yell at me.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Matt T. Rosenberg, MD, earned his medical degree at the University of California, Irvine, where he trained in general surgery. He also trained in urologic surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston before changing fields to general practice. Dr Rosenberg has a special interest in the medical management of urologic diseases and has authored or coauthored articles appearing in Urology, The Journal of Urology, BJU International, The International Journal of Clinical Practice, and other peer-reviewed journals. He now practices in Jackson, Michigan, serving as Medical Director of Mid-Michigan Health Centers, and on staff at Allegiance Health, where he served as Chief of the Department of Family Medicine from 2003 to 2006. Dr. Rosenberg is a Senior Editor at the International Journal of Clinical Practice and is Founder and Chairman of the Urologic Health Foundation, a nonprofit group dedicated to the education of primary care physicians in the field of genitourinary disease. In 2011, he was appointed by the AUA Office of Education to be the Coordinator of Primary Care Education.